Arthur Evans: Making a Museum and a Civilization

Research Assistant for the Oxford and Empire Network, Haley Drolet, who completed a master’s in Classics from King’s College London, reflects on how different concepts of empire shape archaeological research as well as museum displays.

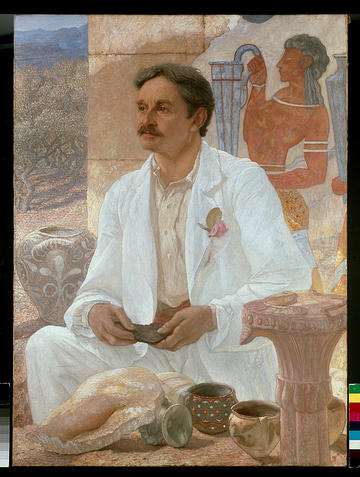

Richmond portrait of Sir Arthur Evans © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

The Ashmolean Museum holds the largest collection of Minoan artifacts outside Crete itself. This is due to the influence of its former Keeper, Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941). In fact it was during Evans’s tenure that the Ashmolean moved from Broad Street to its much bigger premises in Beaumont Street and really became an art and archaeology museum. Among Evans’s most significant acquisitions were of course the many Minoan artifacts he brought to Oxford from his excavation at Knossos.

When asked to write a review of the third volume of Evans’s The Palace of Minos at Knossos, Emeritus Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Oxford, Percy Gardner, wrote:

By slow degrees, Evans has succeeded in recovering in a great measure the architecture, the art, the manners and customs, the physical type, the religion, of the great civilization of which that revealed at Mycenae was but a late offshoot, a civilization contemporary with the mighty empires of the East, and in some ways more interesting than any of them, since it is more European, more in the line of our civilization and progress.

More than a hundred years later, we think of Evans’s work on the Minoans not so much as a recovery than as a process of invention. When you walk into the Aegean World exhibition at the Ashmolean, one of the larger objects you will see on display is an oil painting of Evans. The portrait was painted by his friend Sir William Blake Richmond in 1907 and depicts a congenial Evans set against an imaginary Cretan landscape.

According to the museum’s label, Evans is posed in front of ‘a somewhat freely interpreted reconstruction of the ruins at Knossos’. What do they mean by freely interpreted reconstruction? Well, they are alluding to the fact that Evans not only unearthed the site at Knossos but that he also began to reconstruct it physically and that this reconstruction was guided more by his own ideas than by existing physical evidence.

For Evans, Minoan society was marked by its lack of violence (with no need for physical fortifications) and by strong traces of an earlier matriarchal phase in human cultural evolution. The idea of a matriarchal period had been developed in Bachofen’s Mother Right of 1861, and became widespread, found for example in Friedrich Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Evans, not unlike Heinrich Schliemann before him, approached ancient Aegean civilization with preconceived notions of what he wanted to find. At Knossos he found his utopian empire.

In a world steeped in the brutalism and consequences of empire-making, was Evans simply looking for an alternative? He certainly cared about the cause of those oppressed by the Ottoman empire and then later the Austrian empire, as evidenced by his writings and extensive personal involvement in the Balkans. However, it's less clear what he made of his own country’s empire. Was he a Liberal imperialist attempting to justify the existence of the British Empire by on the one hand contrasting it with the Ottomans and on the other comparing it to the Minoans?

In his creation of the Minoan Age, it’s not hard to see parallels with the Liberal ideal of the British empire in the late nineteenth century: his Minoan civilization was peaceful, protected by the sea and by its sea power; its imperial yoke was light; its expansion was fueled by commerce; it boasted high levels of bureaucratic and legislative sophistication, and achievements in the arts and sciences.

Evans’s vision of the world of Knossos proved powerful and influential, although it has also been vigorously questioned. For example, Robert Graves, who studied English at St John’s College, Oxford, was captivated by the idea of a primitive matriarchal religious system as laid out in his seminal 1948 book, The White Goddess. The following year Graves published a novel imagining a futuristic version of Evans’s utopian Minoans, complete with matriarchal structures and goddess-worship. Seven Days in New Crete both entices the reader into Evans’ utopia and encourages them to question its legitimacy as darker motives are revealed. From the start scholars have challenged Evans’ picture, questioning for example the peaceful nature of Minoan society, some even suggesting that Minoans practiced ritual human sacrifice and cannibalism.

While he may provide an interesting contrast with contemporaries like Cecil Rhodes (whose support of the British empire was explicit), Evans and those in his circle still insisted on using archaeology to demonstrate the primacy of western civilization.

It is important that we question the assertion Percy Gardner made when claiming that ancient Minoan civilization was more interesting, more European, and more in line with progress than the mighty empires of the East. When I walk into the Aegean World exhibition as a white American am I meant to view it as belonging exclusively to a western heritage of which I am the current incarnation? This seems to be how Percy Gardner and Arthur Evans understood it.

Just like the excavation at Knossos, museums are spaces of reconstruction, places where our engagement with the past is curated by the present. While curators today are more careful to achieve neutrality than they once were, we should never be afraid to investigate existing assumptions which have become immortalized in our museums.

So if you have a chance to visit the Ashmolean either virtually or in person, consider the original curator behind its incredible collection of bronze-age Cretan artifacts. Consider what other empires (Roman, Japanese, British) are represented in the museum. What is and isn’t being conveyed about these imperial histories? How do these exhibitions contribute to our understanding of empire today?

Suggested Reading

Brown, Ann, Arthur Evans and the Palace of Minos, (University of Oxford Ashmolean Museum, 1983)

Gere, Cathy, Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009)

Harden, D.B., Sir Arthur Evans 1851-1941: A Memoir, (University of Oxford Ashmolean Museum, 1983)

MacGillivray, J.A., Minotaur : Sir Arthur Evans and the archaeology of the Minoan myth, (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000)

Marinatos, N., Sir Arthur Evans and Minoan Crete: Creating the Vision of Knossos, (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015)

Suggested Resources

The Ashmolean’s Aegean World exhibition

Sir Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum

The HEIR Project. The Historic Environment Image Resource, contains digitised historic photographic images and other resources such as images of drawings and maps from all over the world dating from the mid-19th century onwards. Search for Knossos to see early photographs of the excavation!