HEIR archive exhibition; Women and the Camera

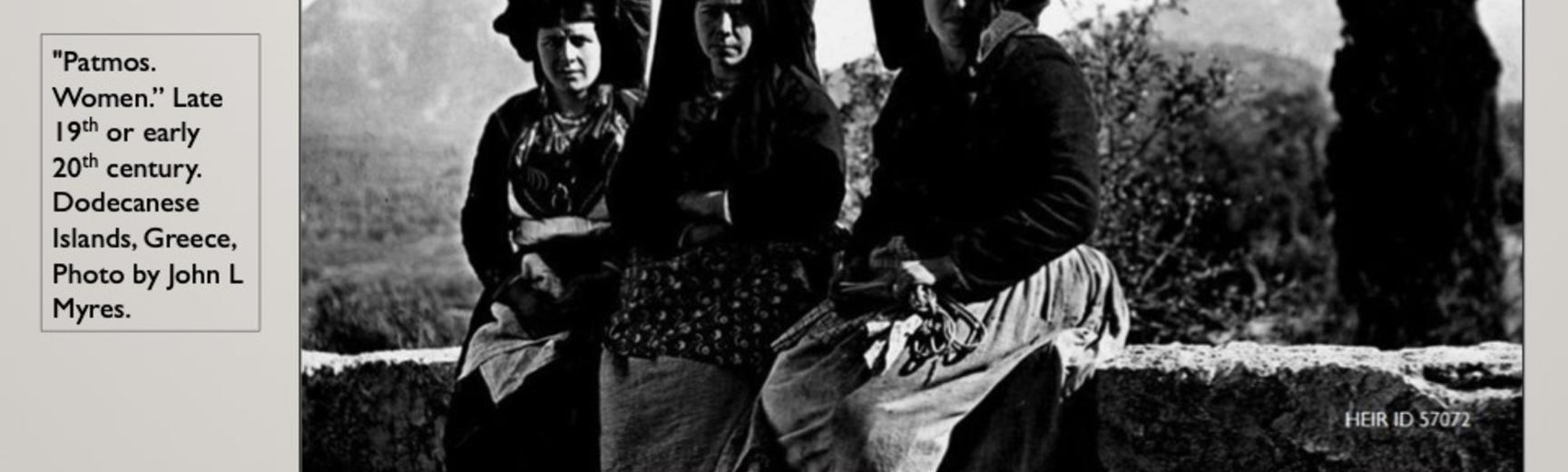

This photo presentation uses images from the HEIR Project digital image archive of the Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford. It explores the relationship over the past 150 years of women from around the globe with cameras, both as subjects in front of the lens and as photographers.

The pictures come from selected university teaching collections and images donated to the HEIR Project. Most are from obsolete photographic media such as glass plate negatives, film negatives, lantern slides or 35 mm images, so had been unseen for decades before their revival as digital scans by the HEIR Project.

Download the Exhibition

Some Thoughts about Women, Cameras and the British Empire

Curator, Dr Janice Kinory reflects on the exhibition.

The HEIR (Historic Environment Image Resource) Project digital image archive is a collection of more than 32,000 pictures that come from technologically obsolete teaching collections previously used in a number of departments of the University of Oxford and private collections that complement the university images. Based at the archive of the School of Archaeology, the pictures include historic buildings and places, images taken during travel and excavations, artworks, archaeological artefacts, drawings, maps and other lecture illustrations. The pictures date as far back as 1860, though most are after 1880, and span the globe with a particular emphasis on the classical world and the former British Empire countries.

People in the pictures were often considered irrelevant to the “true” subject of these images, mere props holding an object of interest or intrusive, possibly lured by the rare excitement of a photographer at work. Yet our modern eyes find those long-gone individuals of great interest, sometimes more so than the official subject of the view. If you look deeply, you find details about the world these people lived in as well as insight into the mind of the photographer. With the long exposure times of the early images, none of these pictures are the casual snapshots so common now.

With travel difficult and expensive, for most British people their views of the empire came from written sources and photographs. For that reason, empire photos are not neutral. They served to underpin the supposed “civilising” mission of the empire. They often emphasized how unlike the British the empire’s other citizens were. The University of Oxford was a central part of the network producing colonial administrators and technical experts for the empire. Pictures used as part of the university’s teaching material formed part of the basis for the conscious and unconscious biases of these future colonial administrators and their future decisions and actions.

In early 2020 the writer learned that the Photo Oxford 2020 exhibition was planning to focus on a century of women as matriculated students in the university. With thousands of images in the collection, I volunteered to put together a presentation about university women using HEIR images. It came as a bit of a surprise when trying to assemble the presentation that it became obvious the collection had very few images showing women known to be either university staff or students. Even the pictures from St Hugh’s College, formerly one of the four women’s colleges within the university, had provided only two images of women, and one of these was a major donor rather than a student. Yet there were thousands of photographs of women in the collection and a large group which were taken by women.

The presentation then morphed into a wider view of women’s relationship with cameras. The teaching images in HEIR from the former colonies provide a contemporary view of the empire designed to prepare young men for their overseas tasks. The early pictures come from a time when the British empire, sexism, the class system, racism and white privilege were accepted without challenge by those benefiting from the system, the same people who could afford foreign travel and cameras. These unchallenged assumptions inevitably impacted the selection of photographic subjects, the framing of images and their interpretation as teaching materials. How are these assumptions reflected in the pictures of the “Women and the Camera” exhibition?

Read Dr Kinory's full article here on our Research page to find out more.