Geography and Empire: Sir Halford Mackinder in Oxford, 1880-1905

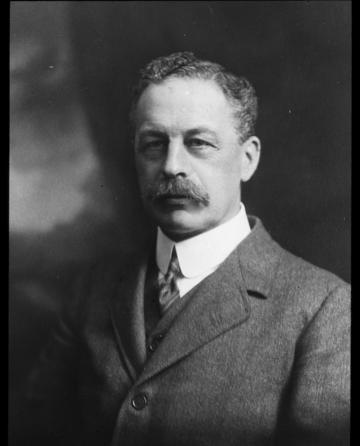

Sir Halford Mackinder (1861-1947)

The Historic Environment Image Resource (HEIR), University of Oxford

Sir Halford Mackinder (1861-1947) is mainly remembered today for his famous lecture on “The Geographical Pivot of History” delivered in front of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in 1904. Later revised and expanded, this bold vision of Central Asia as the core of world politics has influenced many scholars and politicians during the twentieth century, especially in the United States, contributing to the success of geopolitics as a field of study in international relations. Yet Mackinder was a much more complex figure than the simple geopolitical “prophet” often cited in articles or podcasts about world politics. In almost six decades of public life, he was a teacher, an explorer, a politician, an academic administrator, and a diplomatic envoy in revolutionary Russia. Therefore, his legacy has been significant in many ways, though at heart he remained an academic geographer committed to the defence of the British Empire on the international stage. This peculiar combination of geographical scholarship and imperial activism was already visible in Oxford, where Mackinder spent the most part of his early life and worked hard to establish geography as a respected academic discipline.

Humble beginnings

Mackinder arrived in Oxford in 1880 to study natural sciences with renowned biologist H.N. Moseley, who exerted a considerable influence over the young student. During his time at the university, however, Mackinder also became fascinated by the historical works of J.R. Seeley and E.A. Freeman, which presented an “organic” interpretation of the national past and emphasized the superiority of “English civilization” as the main justification for Britain’s imperial rule in Africa and Asia. He also participated to the political debates of the Oxford Union and absorbed the notions of “service” and “duty” typical of the Victorian era. After graduation, these notions led him to become a teacher for the Oxford university extension movement, which aimed to bring higher education to the working-class families of England’s industrial districts. The work was poorly paid but allowed Mackinder to develop his skills as a lecturer and public speaker, paving the way for his future academic career. Moreover, it also convinced him of the good prospects of geography as a field of popular education, thanks to the scientific novelty of the subject and to the public campaign launched by the RGS in favour of a more rigorous geographical training in schools.

The house of Mackinder's family at Gainsborough, Lincolnshire

The Historic Environment Image Resource (HEIR), University of Oxford

In 1886, Mackinder joined the Society and started to delineate geography as an intellectual bridge between the sciences and the humanities, focused on the complex interaction of humanity and nature over the physical earth. His model were the new geographical theories developed in Germany by Ferdinand von Richtofen and Friedrich Ratzel, which tended to examine human activities within their natural environment and to look at the various features of the physical world as an organic whole. Inspired by his German colleagues, Mackinder believed that the geographer should be “a man of trained imagination”, capable of “visualizing forms and movements” in space and of reading maps in a dynamic way.[1] These skills could then be taught to both politicians and average citizens, preparing them to solve the numerous “problems” (political, economic, military) imposed by geography to their country. In an age of fierce international competition, Mackinder saw geographical knowledge as a powerful asset for the preservation of the British Empire, and he worked hard to establish its teaching in schools and universities alongside history and philosophy.

Of course, Oxford was at the centre of this effort, due to Mackinder’s involvement with the university extension movement and to the personal networks he had created during his university years. In 1887, he got an official position as reader in geography and received regular funds by the RGS to promote the teaching of the discipline in academia, but the task remained difficult and unrewarding. Mackinder’s first lecture in Oxford, for example, was attended only by three students and cooperation from his academic colleagues was often minimal or non-existent.

After a couple of years, however, the situation improved and Mackinder was able to attract new students from the university extension programme, including several women. By 1895, he had built a small but dedicated staff who delivered lessons on both physical and historical geography, stressing the dynamic and interdisciplinary nature of the subject to an ever-growing number of students. But Sir Clements Markham, the President of the RGS, was not satisfied with these results. He still viewed geography as closely linked to exploration and started to cut the financial support for the educational projects organised with the university extension movement. Forced to defend his work, Mackinder took a bold step and proposed the creation of a proper School of Geography in Oxford, supervised by a committee partly drawn from members of the RGS. He also organised an expedition to climb Mount Kenya, in East Africa, with the intention of proving his “geographical skills” to the old guard of the RGS. After some discussions, Markham gave finally his support to Mackinder’s project. In early 1899, the university also accepted the creation of the School and appointed Mackinder as its first director with the tasks of designing the curriculum and preparing the staff for their examination duties. A few weeks later, he left Oxford to launch his climbing expedition in East Africa.

The ascent of Mount Kenya and its aftermath

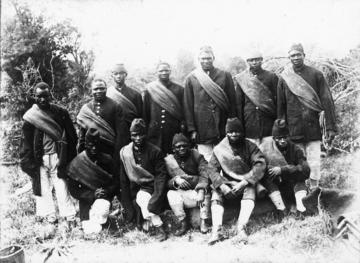

Landing in Mombasa, Mackinder found a country ravaged by famine and received the necessary supplies for his expedition only after some negotiation with local colonial authorities. He and his party proceeded then to Nairobi, where they recruited native guides and porters for the march to Mount Kenya. The expedition moved northward in late July, hoping to reach the mountain before the end of summer, but the travel was not a pleasant one: porters were often whipped for minor disciplinary infractions, while relations with local villages were tense due to mutual mistrust and the racist attitudes of the white members of the expedition. The same Mackinder expressed sometimes open contempt for his Swahili porters, describing them as “slaves” or “faithful dogs”.

Swahili porters dressed in Alpine clothes for the climbing of Mount Kenya, 1899

The Historic Environment Image Resource (HEIR), University of Oxford

After four weeks of march, the expedition reached the surroundings of Mount Kenya and began the ascent of its peak, despite the relative lack of food supplies and proper climbing equipment. The task was successfully completed on September 13, with Mackinder exhilarated by the natural spectacle of the glacier summit at noon. However, eight porters were shot for insubordination and the return to Nairobi was plagued by the same problems and tensions of the outward journey. But Mackinder did not show any regret for the human cost of his adventure. By early October, he was back in Oxford to resume his duties as director of the new School of Geography, ready to exploit his East African “triumph” for the advancement of his educational plans.

The first move was to appoint a capable assistant reader and lecturer for physical geography. Mackinder’s choice fell on Andrew John Herbertson, who was a former assistant of sociologist Patrick Geddes at Edinburgh. Herbertson was mainly interested in regional geography and this provided a valid complement to the more global outlook of his senior colleague. In 1901 the School held its first diploma examination and four candidates were successful, leading to a further expansion of the institute’s teaching programme.

At the same time Mackinder’s skills as a lecturer attracted growing numbers of students, who enjoyed the clarity and precision of his presentations. The School’s reputation continued to grow, but the director’s mind was already elsewhere: in 1902 he published Britain and the British Seas, a widely acclaimed book on the geography of the British Isles, and took new teaching duties at the London School of Economics (LSE), thanks especially to his close friendship with Sidney and Beatrice Webb. One year later, Mackinder became officially the new director of the LSE and this limited his involvement in academic activities at Oxford, though he was dutifully reappointed as reader in geography by university authorities. By 1905, the School was attended by more than 300 students and released regular diplomas and certificates at the end of the year. These results helped to launch a bid for the establishment of a full professorship of geography at the university. There were some quarrels about the initiative, but the position was finally awarded to Herbertson, who enjoyed the support of most of his colleagues. After this development, Mackinder left the School to pursue his growing political interests, which led him to join the tariff reform campaign of Joseph Chamberlain and to become a Unionist MP for Glasgow in 1910. From 1920 to 1939, he was also chairman of the Imperial Shipping Committee, putting his academic expertise and organisational skills in direct service of the British Empire.

Mackinder in Oxford: a mixed legacy

Mackinder with the staff of the School of Geography, 1901

The Historic Environment Image Resource (HEIR), University of Oxford

Mackinder’s relationship with Oxford was complex and ambivalent. On the one hand, the university was pivotal for his political and intellectual formation, nurturing both his patriotic enthusiasm for the British Empire and his ambitious view of geography as a broad universal subject. The RGS lecture of 1904 would have been impossible without the cultural influence of J.R. Seeley and the other great exponents of the Oxford historical tradition. As their most celebrated works, it was a clear attempt to paint the history of the world on a large canvas, providing useful and reassuring answers to a nervous imperial nation. At the same time, Moseley’s mentorship gave a more defined direction to Mackinder’s scientific interests, leading him to appreciate the rich complexity and dynamic nature of the physical world. His personal debt to the university was thus very significant. Yet Oxford was also a source of deep frustration for Mackinder. His efforts to establish geography as a major discipline were often met with indifference or hostility by university authorities, and the School’s prospects after his departure remained quite precarious for a very long time. Despite his brilliant talents, Herbertson struggled to expand the activities of the institute and his premature death in 1915 almost led to the demise of Mackinder’s work. A full professorship and a proper honors degree in geography were recognised only in the 1930s. Compared to his contemporary experience at the LSE, Mackinder’s achievements in Oxford were limited and relatively unsuccessful. But the fruits of his work remained and today the professorship of geography at the university is still named in his honour.

Simone Pelizza

Simone Pelizza graduated in History at the Catholic University of Milan and then moved to the University of Leeds to work on his PhD thesis on the life of Halford Mackinder. He was successfully awarded his doctoral degree in 2013 and has written various articles and book reviews on the international history of the early 20th century. Today he works as a freelance translator but continues to be interested in geopolitical ideas and international relations. He is a member of the Italian Society for Military History and writes articles on current global affairs for the Italian magazine “Il Caffè Geopolitico” (www.ilcaffegeopolitico.net). He lives in St Albans, and can be contacted at pelizza.simon[at]gmail.com.

Further readings

Brian W. Blouet, Halford Mackinder: A Biography (Austin, TX: A&M University Press, 1987)

Gerry Kearns, Geopolitics and Empire: The Legacy of Halford Mackinder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Halford Mackinder, The First Ascent of Mount Kenya (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1991)

W.H. Parker, Mackinder: Geography as an Aid to Statecraft (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982)

Simone Pelizza, ‘Geopolitics, Education, and Empire: The Political Life of Sir Halford Mackinder, 1895-1925’ (PhD Thesis: University of Leeds, 2013)

[1] H.J. Mackinder, ‘Modern Geography, German and English’, The Geographical Journal, 6 (1895), pp. 368-9.