The Indian Institute: Monier-Williams and Empire

Dr Gillian Evison, Keeper (or Librarian) of Oriental Collections at the University of Oxford's Bodleian Libraries, outlines the history of the Institute from its optimistic beginnings as a colonial centre of instruction about all things Indian to its disintegration under the pressures of battles for real estate and changes in the way that the University of Oxford thought about its teaching of Indian subjects.

The full text of Dr Evison's research paper is freely available through ORA (Oxford University Research Archive) here.

The Indian Institute, Broad Street, Oxford

The building of the old Indian Institute, now the home of the Oxford Martin School, is the surviving remnant of an ambitious research institution set up in 1884 by the Boden Professor of Sanskrit, Sir M. Monier-Williams dedicated to the learning and literature of India. Some traces of the former use of the building remain and both the Sanskrit inscription inside the front door and the elephant weather vane on the roof bear testimony to the Indian Institute’s former life as a centre for Indian studies. The majority of the rarest eighteenth- and nineteenth-century publications in the Bodleian’s South Asian collections have bookplates showing that they were originally part of the Institute’s library, giving some idea of the wealth of printed resources available to members of Sir Monier-Williams’ research institution before the dispersal of its library, museum and teaching staff to various other locations in the University in the 1960s.

The Indian Institute was the brainchild of the Boden Professor of Sanskrit Sir M. Monier-Williams. His appointment to the Boden Professorship was somewhat controversial. He was born in India in 1819, where his father was Surveyor General, but he returned to England as a child when his father died. He entered Balliol College but feeling no vocation for the church, for which his family had intended him, he left before taking his degree in order to enter Haileybury College and prepare for service with the East India Company as a writer. He trained for the service at the college from January 1840, and he passed out head of his year. It was whilst at Haileybury that he started to study Sanskrit little knowing that it was to form the substance of his future career. In 1843 he won the Boden Sanskrit scholarship and after graduating in 1844 was immediately appointed professor of Sanskrit, Persian, and Hindustani at Haileybury, a post that he held until 1858, when the college was closed in the wake of the Indian mutiny and the teaching staff were pensioned off.

In 1860, with the death of Horace Hayman Wilson, the prestigious and highly paid Boden Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Oxford became vacant. The Sanskrit Chair had been founded by Colonel J. Boden for “the conversion of the Natives of India to the Christian Religion.”[1] Boden Professors at this time were elected by all the M.A.s of the University3 and as Convocation had 3,786 members the election was contested as if the protagonists were prospective members of Parliament.[2] After a somewhat controversial campaign, in December 1860 Monier-Williams was elected with a majority of 223 out of a total of 1433 votes recorded.

At his inaugural lecture Monier Williams set out the evangelical agenda which had carried the day for him:

“A great Eastern empire has been entrusted to our rule, not to be the theatre of political experiments, nor yet for the sole purpose of extending our commerce, flattering our pride, or increasing our prestige, but that a benighted population may be enlightened, and every man, woman, and child ... hear the glad tidings of the Gospel.”[3]

In his view India, of all British possessions, was the most inviting and interesting for the missionary. It was not a country of savage tribes who would melt away before superior force and intelligence of Europeans but the home of a great and ancient people. These inhabitants traced back their origin to the same Aryan stock as the Europeans and had attained a high degree of civilization when Europeans were still barbarians. India had had a polished language and literature when English was unknown. It was for Europeans, indebted to this ancient civilization, to unearth the fragments of truth, buried under superstition, error and idolatry and to help India return to its former place amongst the foremost nations of the earth. He had to acknowledge that it was unlikely that missionaries would ever encounter Hindus who could understand Sanskrit but nevertheless, loyal to the beliefs of the Chair’s founder, stoutly maintained it was the key to understanding Hindu civilization.

In addition to his evangelical agenda, Monier Williams had not forgotten his days as the Professor of Sanskrit, Persian, and Hindustani at Haileybury. He began to see the possibilities afforded by Oxford for filling the educational vacuum that had been left by the closure of the East India Company College. As he was later to describe in the lecture How can the University of Oxford best fulfil its duty towards India,[4] Indian Civil Service Probationers were selected by an annual competitive examination for 17 to 19 year olds. About forty were selected out of two to three hundred candidates and during two years of probation were expected to sit a number of examinations in London. During the period of probation they were expected to reside in one of eight Universities approved by the Secretary of State for India, namely, Oxford, Cambridge, London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, St. Andrew’s and Dublin. Whilst at the University, they were subject to University discipline but not under formal academic supervision of any kind. In Monier William’s view, the fact that they simply resided at University but did not take any University examinations meant that they gained little from their experience of University life. The unsatisfactory support for I.C.S probationers was particularly visible at Oxford as its proximity to London made it an extremely popular choice for residency.

In addition to the unsatisfactory support for I.C.S. probationers, Indian students had started coming to England and were mostly studying without supervision. Among those in Oxford about half had no College attachments and Monier Williams felt there was a grave risk that after being cast adrift in England Indian students would return home deteriorated in character rather than improved.

In 1875 he persuaded Congregation to pass three resolutions: first that arrangements be made for I.C.S. probationers to reside at the University; second that University teachers should be appointed in certain branches of training required by them: and third that the B.A. degree be brought within their reach.

Proposals

In order to provide a stable study environment for both I.C.S. probationers and Indian students, he formally proposed the foundation of an Indian Institute at a Congregation held on May 13th 1875. The purpose of the Institute was to form a centre of teaching, inquiry and information on all subjects relating to India and its inhabitants. It was to restore among the I.C.S. probationers the old community spirit of the East India Company's College at Haileybury and would promote the welfare of Indians in Oxford. In addition it would propagate a general knowledge of India among Oxford's ordinary students some of whom might go on to exercise control over India's destiny in Parliament. Before the advent of submarine telegraphy, district officials had a great deal of autonomy but with swifter communication channels, London government had an opportunity to interfere, for good or ill, as never before. As Monier Williams tactfully remarked in his speech at the opening of the new Institute “the interposition of an all-powerful Assembly, acting with the best intentions, but not always according to knowledge, is apt to cause administrative complications.”[5]

The new Institute was to have lecture rooms, staff rooms, accommodation for Indian students and visitors and a library which was to "offer for daily use a collection of Indian manuscripts, books, maps, and plans, many of them too rare and costly to be procurable by private means. Its Reading-room will be supplied with all kinds of Indian newspapers and periodicals, some of them in the native languages."[6] The Institute was also to have a Museum that was to present a typical collection of specimens which would give a concise synopsis of the country and its material products, its people and their moral condition. Monier Williams sought to reassure Congregation that the sole purpose of this Institute was to be the prosecution of Oriental research and not to attract “mere sight-seers, curiosity- hunters, and excursionists”.[7]

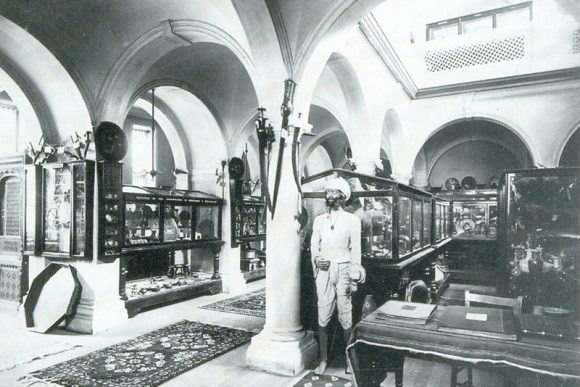

The Indian Institute Museum with its original display, c. 1898-99

Monier Williams’ first trip to India was a success. He held meetings in the major cities in the north including Bombay, Calcutta and Delhi, explaining his proposal and asking for aid. The Prince of Wales, who was at the time in India, pledged his support, along with Lord Northbrook, the then Governor-General, and many members of the Civil Service. A number of Indian princes were also persuaded to join the subscription list. A second trip in the South of India and Ceylon followed towards the end of 1876 in which he was to receive similar encouragement. In addition to official support and money, he also received gifts of books, manuscripts and objects for the proposed new museum and library. Monier Williams followed his two Indian trips with a series of lectures and addresses in London and Oxford. In these he promulgated his vision of Indian studies becoming part of every University curriculum and the creation of a number of Institutes devoted to the dissemination of correct information on Indian matters, of which Oxford’s proposed Indian Institute was to be but the first. The fund raising campaign received further momentum with the official approval and support of Queen Victoria and the royal princes.

In Oxford the Master and Fellows of Balliol were particularly sympathetic to Monier William’s great enterprise. It was Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol who offered every candidate who passed the I.C.S. examination a place in Balliol and it was Balliol College Library that provided a temporary home for the books and manuscripts that had been collected for the new Institute. Initially it was planned that the Institute itself would be part of Balliol but Jowett had made himself unpopular by attaching too many of the staff appointed by the University to his college and the idea was abandoned in favour of making it a University institution.[8] In his book Oxford and Empire, Richard Symonds suggests that the Indian Institute would have had a better chance of development had it been attached to Balliol.[9] Certainly it is likely that Balliol would have been prepared to make up some of the shortfall in running costs which quickly became apparent after its opening. A college-based Institute might also have received stronger academic direction, and been prevented from sliding into the government club about which Edward Thompson was to be so scathing in the 1930s.

The Institute began its life in rooms hired at no. 8 Broad Street, opposite to Balliol College but in 1880 Convocation approved the plan for an Indian Institute and granted a site in the Parks along with an Endowment of £250 per annum from the University Chest, payable from the date of its opening.

There was considerable opposition to the new Institute being built in the Parks and negotiations were then started with the Fellows of Merton College who consented to part with a site in Broad Street for the sum of £7,800. The Prince of Wales laid the foundation stone of the building in 1883, acting with full Masonic ritual, and the University statute governing the Institute was passed in 1884.

The Building

Elephant carving, Indian Institute

The building, consisting of lecture rooms, a library and museum, was not completed until 1896 since some of the site was held by leaseholders and the leases did not come up for renewal until 1892. Monier Williams had to raise more money to purchase this land from Merton College and managed to secure the £1,400 needed from Sir Bhagvat Sinhjee, Thakur of Gondal. The architect was Basil Champneys with the carving being executed by a Mr. Aumonier.

At the very first recorded meeting of the Indian Institute Curators on 5 Nov 1884 the third item on the agenda was a discussion about the insufficiency of endowment of £250 per year and the problem of under-funding appears with monotonous regularity in the minutes from then on.

A manuscript volume held in the Ashmolean lists the objects collected for Monier Williams between 1883 and 1885. They vary from the eccentric, such as the three blown crocodile eggs and granite stone for scrubbing elephants from Travancore to highly professional selections from the most knowledgeable experts of the day, such as the collection of several hundred examples of handicrafts chosen by the Madras Museum.

When the completed Indian Institute was finally opened the museum installation was carried out by Dr. H. Lüders assisted by Mr. Long of the Pitt Rivers Museum, with the aid of a grant from the University.[10] The Bodleian has a number of archival photographs, which must have been taken soon after and show a space crammed full of wooden cases, rugs on the floors and walls and costumed dummies. An entrance corridor contains several small stupas from Bodhgaya, a model of emperor Hamayun’s tomb and a couple of stuffed yaks.

As in so many other aspects of the Indian Institute, the lack of financial provision soon told. There was no money to support a full-time curator so its direction was left entirely in the hands of the Boden Professor of Sanskrit. Apart from the fact the Boden Professor had many other duties, appreciation of India’s linguistic and literary achievements rarely went hand in hand with an appreciation of Indian art. The minutes of the Indian Institute Curators show how the museum was from the first the poor relation of the Institute’s library. Apart from acceptance of donations from ex-I.C.S. officers and old India hands, there was little consistent policy concerning the museum in the years that followed Monier-William’s death in 1899.

While the founder of the Institute’s philological and literary interests ensured that the Library received more attention from the Curators than the Museum, its financial situation was no better and it relied on inadequate grants and donations. The two biggest donors of books to the library were Monier-Williams himself, who gave his own library of between 3 and 4,000 volumes, and the Rev. Solomon Caesar Malan who donated his collection of about 4,000 books to the Institute.

The lack of continuity in the Librarian's post and the haphazard acquisition of gifts did not help the development of the collection and one gets the impression that over time the Curators of the Indian Institute found management of the Library increasingly irksome. In the minutes of a meeting held on Nov. 13th 1924 the Keeper complains that although there is an assistant as well as a chief librarian, he often finds that neither of them are to be found in the library.

On Oct. 26th 1926 Dr. Cowley, Bodley's Librarian, approached the Curators of the Indian Institute with a proposal that the Bodleian should take over the management of the Indian Institute Library. Unfortunately the typewritten and printed papers which outline the proposal are missing from the minutes book so it is not clear what benefits that Dr. Cowley felt the Bodleian would gain from connecting itself with the Indian Institute. The Curators of the Indian Institute came to an agreement in which they paid the Bodleian £275 per annum to connect the Indian Institute Library with the Bodleian as a special department for Indian studies. Dr. Cowley took over management of the library in 1927 and while the Librarian remained to assist him, the assistant librarian was replaced with a Bodleian employee. The Curators of the Indian Institute seem to have done rather well out of the deal because by 1928 Dr. Cowley is complaining that the administration of the Indian Institute Library was by no means covered by their contribution and has involved a considerable expenditure from Bodleian funds. It is interesting that despite the early administrative take over by the Bodleian, it is the Library that seems to have come to symbolize the Indian Institute and form the substance of the 1960s dispute which is still remembered today.

The Institute

The academic programme for the Institute was initially ambitious and inclusive. In his the opening ceremony lecture of 1884 Monier Williams described how the Institute had already appointed a number of teacher in Indian subjects and was able to offer one Indian classical language, Indian Law, History, and Political Economy.[11] Oxford was still missing the Honour School of Oriental Studies that he had proposed in 1875 but this became a reality in 1886, the year in which he was also knighted, taking the name Sir Monier Monier-Williams (presumably because he thought it sounded more impressive than plain Sir Monier Williams). The Institute’s academic programme was intended to be the first step in a process whereby Oxford and other Universities would eventually take over the entire process of educating and examining Indian Civil Service Probationers. The teaching programme would also answer the needs of the future doctors, lawyers and missionaries of the university who would end up working in India. The academic programme was intended to go hand in hand with the interchange of knowledge that would naturally arise from mixing young Englishmen with Indians studying in England. Monier Williams saw the young Indians gaining active dynamic qualities such as courage and determination while the young Englishmen would learn passive qualities such as patience and obedience to authority.[12]

In the early days of the Institute, however, there were insufficient Indian students to provide the kind of counterbalance to the I.C.S. probationers that Monier William’s rosy vision of an East West interchange of moral qualities required. An attempt to secure six Government scholarships for visiting Indian scholars had failed because the Secretary for India overruled a promise made to Monier Williams by the Viceroy, being disinclined to single out Oxford University for special favour.[13] In an article that appeared in the Oxford and Cambridge undergraduate journal of May 10, 1883 the author knew of only three native Indians in Oxford and did not believe there could be more than a dozen.[14] On the other hand there were some 50 I.C.S. probationers at the time of the Institute’s foundation.

The Honours School in Indian studies was short-lived and came to an end in Monier-William's own lifetime. It failed to take off as a popular alternative to Classics for those contemplating careers in India and interest was confined to those had already decided to make India their career, namely the I.C.S. probationers. After a change in the age limits of the Indian Civil Service made it no longer possible for the I.C.S. probationers to stay in Oxford for more than a year, the Honours School was no longer viable.[15]

In 1955 the Hebdomadal Council passed a decree to establish the Oriental Institute, which was to include "full provision for Indian studies." In the Congregation debate, Mr. H.T. Lambrick, Fellow of Oriel College, spoke against the proposal. He did not object to an Oriental Institute but protested that the inclusion of Indian studies would mutilate the Indian Institute and that it would be the story of Naboth’s vineyard all over again.[16] G.R. Driver, Professor of Semitic Philology spoke for the motion. He suggested that the Indian Institute may have been responsible for the decline in Indian studies at Oxford in the last 20 years and assured Congregation that the successors of those who gave money to found the Institute had been consulted and were not unfavourable to the proposals for the Oriental Institute. The decree was passed. A further resolution was then passed to lift restrictions on the use of the Indian Institute and allow the University to make use of any spare accommodation in the Indian Institute exclusive of the library, galleries and rooms already occupied by persons whose work required proximity to the library.[17] The Indian Institute Library was to be allowed to remain because Bodley's Librarian and Curators had adamantly opposed the move of Bodleian material away from the central site and won general support for their position.

In 1964 the Hebdomadal Council started discussing a proposal with Curators of the Bodleian. The proposal was that the Bodleian, which was badly in need of further accommodation, should be offered the Proscholium, to serve as a main entrance and the Divinity School for an exhibition room. In addition the Indian Institute Library was to be moved from the Indian Institute building to a roof extension, which was to be built on the north range of the new Bodleian and joined to deck B, which would be used for open shelf Indian Institute material.

In June 1965 two contentious debates were held on the future of the Indian Institute site. K. Ballhatchet, Reader in Indian History, led the opposition. He argued that the Franks commission had yet to make its recommendations on future provision for the University's administrative requirements. It was therefore not sensible to make provision for administrative offices on the Indian Institute site when the future shape of the administration had yet to be decided. D. Pocock, the Reader in Indian Sociology said that treating India as a branch of Oriental studies failed to reflect equal numbers of research students from other disciplines such as Modern History, Anthropology, Geography and Agriculture and Forestry. He felt that to ally Indian studies so closely with Oriental studies gave a wrong impression to those outside Oxford of the University’s interests in South Asia. It was argued that the Indian Institute site should not only retain the library but also provide rooms to allow for the development of a proper South Asian Regional Studies centre, such as had just been set up by Cambridge.

At the close of the debate, Ballhatchet's amendment to the decree was rejected by 38 votes and the decree was carried by 55 votes. Since the decree had achieved a majority of less than two thirds it had to go to Convocation, the body of all the M.A.s of the University. The voting was again close and the decree was carried by a mere 18 votes.

Conclusion: The Orientalist, his Institute and the Empire

In the popular version of the history of the Indian Institute, the Institute takes a simplified form, just a building and a library, which together symbolize enduring British-Indian friendship and a golden age of Indian Studies in Oxford, brutally torn asunder by an uncaring University. As I hope I have shown, the real the story of the Institute is more complex and troubled. The seeds of its destruction, namely an over-ambitious vision, lack of money, and the focus on a narrow sector of the student population were present from the day it opened its doors. While its demise was not inevitable, it is not as surprising as it might seem to those who have only encountered the popular version of the Institute’s history. Monier-Williams would have been gratified to see the affection in which his expensive bricks and mortar are held today and one cannot but admire his achievement in creating a library, museum, and teaching centre from nothing. Had the Institute had more Keepers of his entrepreneurial flair it might still be in existence today serving students and researchers of the University where once it trained Civil Servants for the Empire.

[1] The Times Wed Dec 22 1830. Notice of the election of the Professorship of Sanskrit in the University of Oxford.

[2]Nirad Chaudhuri Scholar extraordinary : the life of Professor the Rt. Hon. Friedrich Max Müller, P.C. London : Chatto & Windus, 1974 p. 221

[3] Monier Williams A study of Sanskrit in relation to missionary work in India; an inaugural lecture delivered before the University of Oxford, on April 19, 1861. London: Williams and Norgate, 1861, p. 59-60

[4] Monier Williams How can the University of Oxford best fulfil its duty towards Oxford? Lecture given at the opening of the Indian Institute and reported in the Oxford & Cambridge Undergraduates Journal, Oct 16 1884

[5] Monier Williams How can the University of Oxford best fulfil its duty towards Oxford? Lecture given at the opening of the Indian Institute and reported in the Oxford & Cambridge Undergraduates Journal, Oct 16 1884

[6] A record of the establishment of the Indian Institute in the University of Oxford : being an account of the

circumstances which led to its foundation. Oxford : Compiled for the Subscribers to the Indian Institute fund, 1897 p. 4.

[7] A record of the establishment of the Indian Institute in the University of Oxford : being an account of the

circumstances which led to its foundation. Oxford : Compiled for the Subscribers to the Indian Institute fund, 1897 p. 4

[8] Balliol College Minute Book (25 June 1878 and 9 Nov 1878)

[9] Symonds p. 109

[10] J.C. Harle & Andrew Topsfield Indian art in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1987) p. xii.

[11] A record of the establishment of the Indian Institute in the University of Oxford : being an account of the

circumstances which led to its foundation. Oxford : Compiled for the Subscribers to the Indian Institute fund, 1897 p. 42.

[12] A record of the establishment of the Indian Institute in the University of Oxford : being an account of the

circumstances which led to its foundation.Oxford : Compiled for the Subscribers to the Indian Institute fund, 1897 p. 42

[13] Symonds p.111.

[14] Oxford review: the Oxford & Cambridge Undergraduates review. May 10, 1883

[15] Symonds p. 111-112.

[16] Times Wed Jun 1, 1955.

[17] Oxford University Gazette 3 June 1955 p. 1003-4.