The Pitt Rivers Museum Catamaran

Morgan Breene is a DPhil student in Global and Imperial history at the University of Oxford. She studies the British imperial experience of the littoral zone in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Madras (Chennai), and the boats used for crossing from ship to shore. She is also the secretary for the graduate-led Transnational and Global history seminar (TGHS) at Oxford, which hosts seminars on a variety of themes in global history.

Introduction

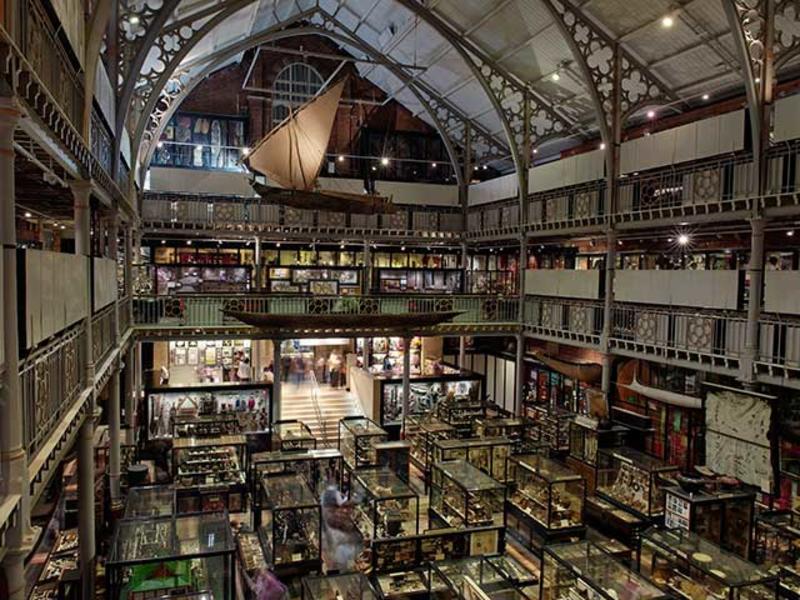

Figure 1 The main hall of the Pitt Rivers Museum. Can you spot the boats? (Pitt Rivers Museum, https://www.glam.ox.ac.uk/pitt-rivers)

Suspended from the middle gallery of the main court of the Pitt Rivers Museum is a collection of watercraft from around the world. Tucked up and out of the way, they blend into the overwhelming atmosphere of collected stuff that the main hall exudes, more backdrop than items on display. Even I, a maritime archaeologist specifically studying native boats in British Imperial contexts, didn’t notice them immediately when I first visited the museum. When I did finally notice them, I found the labels to be more puzzling than enlightening. The location and labelling of the boats, as is the case for many other objects in the collection, has come to obscure, rather than elucidate, their stories and relevance for the museum audience. Such objects have untapped potential as resources for teaching the public about the experience of empire abroad, the modes of collection and acquisition, and the portrayal of empire in Britain. Here, I focus on one of the boats, the Coromandel Coast catamaran, but the arguments I outline are equally applicable to other parts of the collection that are hidden in plain sight, or insufficiently labelled.

The catamaran is a type of fishing boat used for centuries on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka. As a harbour craft, they were critical to the success of Madras (modern Chennai) as an East India Company port in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The particular catamaran in the Pitt Rivers collection is not only representative of such boats, however. It arrived in Britain in a moment of increasing tension between Britain and India, and was most likely donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum at the direction of James Hornell, the foremost British maritime ethnographer of the early twentieth century. It represents an opportunity to think about how objects are labelled, why they were originally displayed, and what stories they can be used to tell.

What is a Coromandel Coast Catamaran?

The Coromandel Coast is a section of the east coast of India within the modern state of Tamil Nadu. The coastline is infamous for its exposure to monsoon winds off the Bay of Bengal and its lack of natural inlets or safe anchorages. Despite this, Madras was also the English East India Company’s first secure foothold in India.i It quickly became a powerful seat of regional government, and as the city bordered significant textile producing and diamond mining regions, was an important site for the export of finished goods to Britain. Prior to the construction of a modern harbour in the late nineteenth century, transporting such lucrative cargoes from shore to ship was a dangerous proposition. Communication with shore through unpredictable surf was limited to certain types of watercraft that could survive sustained wave action. One of those types of watercraft was the catamaran.

Figure 2 The Pitt Rivers Catamaran suspended from the balcony. Photo by author.

The Pitt Rivers catamaran is an example of the specific type of catamaran built and used at and around Madras.ii This boat type was first documented by European visitors in the seventeenth century, but had likely been in use for centuries as a fishing craft.iii Such catamarans typically consisted of three logs bound together using coconut-fibre coir, or rope. Catamarans varied in size, and depending on their length, would be crewed by one or two men with paddles. Between trips, catamarans at Madras would be disassembled and laid on the beach to dry fully.iv

During East India Company rule and then as part of the British Raj, catamarans and catamaran-men at Madras were employed to maintain written communication between ships and the shore, as lifeguards during dangerous passenger crossings in larger masula boats, and to salvage lost goods and anchors. Catamaran-men would carry messages in their water-proofed hats through nearly any storm or surf conditions and were essential to the smooth running of the port, evidenced by the medals they were awarded for lifesaving and the pension funds established for ‘decayed catamaran-men’ in the late eighteenth century.v In the latter half of the nineteenth century, as harbour installations were constructed and the need for catamarans declined, catamaran-men rejoined the fishing fleet and their boats once again came to be viewed as only a traditional fishing craft, rather than a harbour boat. Catamarans used for fishing in the early 20th century were equipped with masts, sails, and rudders for longer journeys further offshore—the Pitt Rivers example was donated with these additions, but they are not on display with the hull.vi

The Pitt Rivers Catamaran

The Pitt Rivers catamaran, accession number 1924.44.31, is labelled as follows:

‘ASIA, INDIA, MADRAS, COROMANDEL COAST. Catamaran made from logs of malai vemboo (melia azedarach) lashed with coir. A man seated on the central projecting logs paddled alternately on either side. Used for surf navigation. Donated by the Government of Madras, 1924.’

This label is notably uninformative. It provides some basics—the construction material, mechanics of use, and date of donation—but this information isn’t engaging; it doesn’t facilitate any kind of connection or reaction in the viewer. Without dates, the ambiguous tense of the text unmoors the boat in history. In reality, it is representative of a type that was used widely at the time of its donation, and well after. It doesn’t orient the viewer in space, using the outdated ‘Madras’ rather than Chennai and ‘Coromandel’ rather than ‘southeast’ coast, both names that the casual viewer might not recognize. The label also doesn’t explain what the boat was used for—‘surf navigation’ is not an end in and of itself—why, for instance, were people even trying to ‘navigate the surf?’ For sustenance? Communication? Travel to other coastal settlements?

Focusing on who donated the boat and when just adds to the confusion. Why did the government of Madras have this boat? Why was it brought halfway around the world to the Pitt Rivers? What is significant about the 1924 date?

The online catalogue, for the dedicated viewer, reveals slightly more information about the catamaran. It weighs 103 kilograms, and was donated alongside a mast and sail, anchor, paddles, rudder, fishing club, two unidentified pieces of wood, and a pole. The museum’s 1924 Annual Report lists the catamaran as part of a small collection donated by the Government of Madras which also included a dugout canoe made of Palmyra palm, a coconut float for swimming instruction, small dugout for handline fishing, chank-shell baby feeding spout, and amulet of chank shell for warding off the Evil Eye.vii

The most promising piece of information recorded in the catalog is under what circumstances these objects were donated: they arrived at the museum in November 1924 after display at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, which had just closed after its first season.viii The collection represents only a small subset of the material that was displayed by the Government of Madras at the Exhibition, and all of the objects came from the Fisheries department. The only other Indian state government to donate items to the Pitt Rivers on the heels of the Exhibition was the government of Bihar and Orissa, which made a donation of a number of bows and arrows.ix No other material from India brought to the British Empire Exhibition appears to have ended up in the Pitt Rivers collection.

Why does the Pitt Rivers Catamaran matter?

To me, the biggest problem with the current display location of the catamaran and information available about it is that it fails to answer one fundamental question: why should anyone care about it? I find boats fascinating for their diversity of form and the under- recognized fact that, for millenia, the globe over, they were the most complex transportation technology available. But it can be difficult to convey this fascination through just words, or in a static museum setting, where boats are by necessity decontextualized and stilled. How can objects, like boats, that were meant to be used, to facilitate mobility, be adequately displayed and explained in a place where they cannot be used, cannot move?

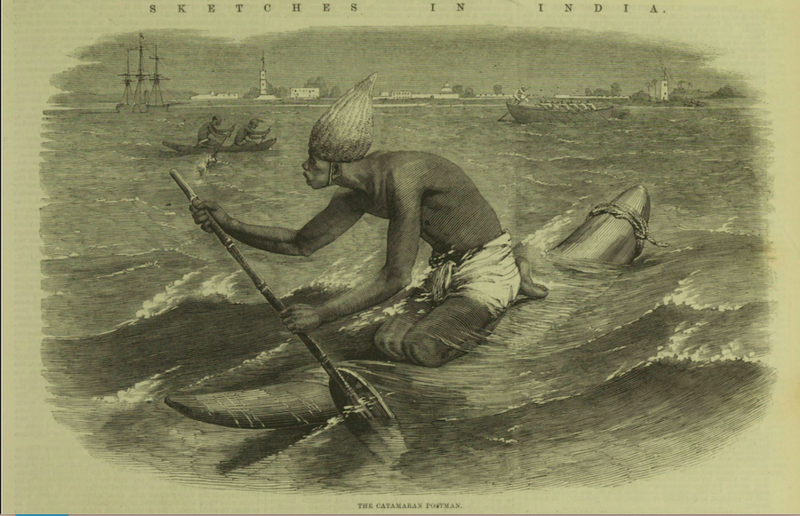

As it stands, the lack of available information or interpretation means that the catamaran, with the other suspended boats, often becomes little more than part of the scenery. Removed from their element, they are displayed as abstract, ancient, ahistorical, primitive or even dead, modes of transportation. But with interpretation, such boats can be restored as the representations of long and rich relationships with the sea that they are. Their current appearance, mere chunks of wood hanging beyond the viewer’s line of sight, fails to capture the dynamism with which such craft moved through the water, the technological prowess and understanding of the limitations of the local environment they entail. Descriptive labels, placed where the viewer will notice them, can explain where, how, when and why the boats were used and collected. Visual representations of the boats in use can help the viewer envision the physical context in which they belong. And the labels can be supplemented and further contextualized by resources such as this blog post, where more information can be given, not only about the boats as representative examples, but as individual objects with their own life histories and importance.

Figure 3 Half-page illustration of a Catamaran-man published in the Illustrated London News, 1858. Such illustrations convey the movement of the catamaran in ways the stationary physical object cannot.

The Pitt Rivers Catamaran and the British Empire Exhibition, 1924

The exact provenance of the catamaran is unclear. It is unknown whether it was ever used as a working boat, or built as a working boat and then selected for the Exhibition before it could be used, or even perhaps was purpose-built for the exhibition as a representative full-sized model. Its life history is currently a mystery until it was chosen for display at the British Empire Exhibition in 1924.

The British Empire Exhibition was held at Wembley Park, one of the last of a long series of Imperial exhibitions in the tradition of the 1851 Crystal Palace Industrial Exhibition. The Exhibition, which ran for two seasons in 1924 and 1925, was designed with two objectives: first, to display the raw materials and manufactures of dominion and colonial states, in order to encourage intra-empire trade in the post-war period; second, to make a show of imperial unity and strength in the aftermath of World War I.x

The message of unity, however, was complicated. Regardless of a professed policy of racial unity across the empire, Indians in particular were becoming increasingly vocal in questioning such a policy that did not align with lived experience. Indian participation in the Exhibition was crucial for projecting an image of imperial unity, though, and despite tensions, planning for an Indian pavilion progressed with only limited objection until the summer of 1923.xi

In July 1923, the Devonshire White Paper was released under pressure from white settlers in Kenya. The paper stripped many of the rights of the longstanding Indian migrant community in Kenya, to the benefit of a much smaller white settler community.xii It also further strained the British government’s relationship with the Indian National Legislature, where even prominent figures who had argued in favour of cooperation lost faith in British promises of racial unity.

Srinivasa Sastri, who had been instrumental in talks of cooperation and India’s participation in the British Empire Exhibition, withdrew from the organizing committee and led calls for an Indian boycott of the Exhibition.xiii While calls for a total boycott were eventually unsuccessful, in the end ‘India’ did not send an exhibit, but rather individual states and manufacturers were allowed to send exhibits at their own discretion. Only one Indian member, Tiruvaliyangudi Vijayaraghavacharya, remained on the organizing committee. He directly attributed the limited and haphazard return on his years of effort to put together an Indian display to the Devonshire White Paper and subsequent fallout.xiv

Many departments in the government of Madras did choose to send exhibits to Wembley in 1924. However, none of the Indian exhibitors chose to reopen for the second, 1925, season.xv The Indian pavilion was purchased by the exhibition organizers and run privately with no government participation or educational displays for the second season.xvi

Figure 4 Image of a fishing catamaran, circa 1920s. From Hornell (1946) Plate 10 A.

This brings us back to the catamaran. The Madras fisheries department chose to participate in the Exhibition, bringing a selection of fish oil, dried fish, and other fishery products, including examples of full-size fishing vessels and models of other watercraft, as well as examples of chank-shell art.xvii Some, but not all, of these objects were donated to the Pitt Rivers museum at the end of the 1924 season. That some of the exhibition material ended up in the Pitt Rivers is not unusual-- Hoffenberg has noted that it was common for dominion and colonial states to donate exhibit material after an exhibition concluded.xviii That all of the material came from a single government agency, however, suggests more than a simple attempt to jettison exhibition material.

James Hornell and the Pitt Rivers Museum

At the time of the British Empire Exhibition, the head of the Madras fisheries department was the Oxford-trained civil servant James Hornell. Hornell’s background was in marine biology, and he had run the fisheries department since 1907. During his time in India, however, Hornell had also developed an interest in traditional boat building practices around the Bay of Bengal.

Between 1920 and his death in 1949, he published a number of articles and books on the development of watercraft in the Indian Ocean and Africa; today he is recognized as the foremost British ethnographic expert on Indian Ocean boats of the first half of the twentieth century. Hornell crafted a global boat building chronology, attempting to demonstrate a steady increase in watercraft sophistication from the dugout canoes of ‘primitive’ cultures to the modern oceanliner.xix He was also well acquainted with the Pitt Rivers Museum and its ethnological mission, having already donated a number of artefacts and objects from his own personal collection at the time of the fisheries department donation in 1924.xx

The decision to deposit some of the fisheries material at the Pitt Rivers was likely made by or at the direction of Hornell. The donated objects align with Hornell’s known research interests and the ethnographical mission of the Pitt Rivers Museum. It is noteworthy that Indian commentators who visited the British Empire Exhibition had criticized the Indian pavilion for ‘primitivizing’ the technology on display, instead of emphasizing the advances being made in the country.xxi Presenting catamarans and dugouts as ‘traditional’ fishing craft and then donating them to an ethnographic museum meant to introduce a British audience to less scientifically/culturally/medically/technologically advanced African, Asian, and North American cultures, would have been in line with Hornell’s views on the evolution of boat building practices and cultural sophistication.

The Catamaran and the Mission of the Museum

The 2017-2022 Strategic Plan for the Pitt Rivers museum is aimed at making the museum a more welcoming, inclusive and collaborative space for all visitors. The ‘Labelling Matters’ project, begun in 2019, is one specific effort aimed at identifying problematic labelling language and ‘find[ing] innovative forms of interpretation to challenge the traditional narratives of [their] current displays.’xxii In the permanent collection, this effort has so far focused on labels that include racialized and derogatory language or narratives. But the labels that have no descriptive language, like that on the catamaran, can also limit engagement and reinforce ‘primitive’ stereotypes. Expanding the breadth of information available to the public and the means of conveying it—not only labels, but blog posts, podcasts, historical imagery, ethnographic film or oral history where it exists—can enrich the museum-goers experience.

Catamaran-men at Madras paddled their craft through waves that average 1.3 meters in height, on any given day, year-round. They paddled miles out to sea, were repeatedly swept off, attacked by sharks, performed daring rescues and recovered valuable cargo from the seabed.

Their experience of catamarans was physical, dangerous, and highly variable, determined by the day-to-day turbidity of the sea. To imagine a comparison between the movement and usefulness of the catamaran as a fishing and harbour craft, and the stillness and timelessness of the display of the catamaran in the Pitt Rivers, shows the difficulty faced in trying to convey use and movement in a museum context, to make objects of mobility meaningful when they cannot move. Engagement and imagination should be encouraged through the provision of more and different information on catamarans in general, and the Pitt Rivers catamaran specifically. This can enrich the viewer’s experience of the catamaran itself, provoke consideration of the means by which we all move through the world, and bring attention to a moment of tension in the fraught British-Indian relationship of the early 20th century.

i Arasaratnam, Merchants, Companies and Commerce on the Coromandel Coast, 1650-1740, 8.

ii Edye, “Description of the Various Classes of Vessels Constructed and Employed by the Natives of the Coasts of Coromandel, Malabar, and the Island of Ceylon, for Their Coasting Navigation”; Hornell,

Water Transport: Origins and Early Evolutions. iii Lockyer, An Account of the Trade in India, 10. iv Graham, Journal of a Residence in India, 127.

v Graham, 128; India Office Records and Private Papers, “Marine Affairs, Catamaran Men, Pension Fund Opened.”

vi Hornell, Water Transport: Origins and Early Evolutions, 60–66.

vii Pitt Rivers online object catalogue search, “Government of Madras.” http://databases.prm.ox.ac.uk/fmi/webd/objects_online.

viii Pitt Rivers Museum object catalogue.

ix Balfour, “Report of the Pitt Rivers Museum, 1924.”

x Stephen, “‘Brothers of the Empire?’: India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25,” 165.

xi Stephen, 166.

xii Hughes, “Kenya, India, and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924,” 75.

xiii Hughes, 77.

xiv Hughes, 75, 81.

xv Hughes, 82.

xvi Stephen, “‘Brothers of the Empire?’: India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25,” 187. xvii Commissioner for India for the British Empire Exhibition, India: Catalogue: British Empire Exhibition, 1924.

xviii Hoffenberg, An Empire on Display: English, Indian, and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War, 13.

xix Hornell, Water Transport: Origins and Early Evolutions; Hornell, “The Ethnological Significance of Indian Boat Building Designs”; Hornell, “Edye’s Account of Indian and Ceylon Vessels in 1833.”

xx Pitt Rivers Museum, “People Database, ‘H’ Names,” The Invention of Museum Anthropology, 1850- 1920, 2012, https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/sma/index.php/people-database/17-people-tables/458-h.html.

xxi Stephen, “‘Brothers of the Empire?’: India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25,” 183.

xxii Laura Van Broekhoven, “Labelling Matters: Reviewing the Pitt Rivers Museum’s Use of Language for the 21st Century,” Pitt Rivers Museum, 2019, https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/labelling-matters.