The Rhodes Statue - and the Rhodes Building

“[F]or the sake of history it is vital that Rhodes must not fall” wrote Rupert Fitzimmons in December 2015, arguing that the statue of the ardent imperialist, Cecil Rhodes, should remain standing on its pedestal above Oriel College.[1] His argument was a common one thrown at ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ (RMF) campaigners that year; that taking down the statue of Cecil Rhodes would amount to an unforgivable change to history.[2]

The statue of Cecil Rhodes outside Oriel might now be considered to be part of Oxford’s history. However, back in 1911 - when the statue was first put up - this could not have been further from the case. Indeed, the erection of the Rhodes statue entailed a dramatic change to Oxford’s landscape - one that reminds us of a longer history of conflict between ‘town’ – the city of Oxford – and ‘gown’ – the University of Oxford.

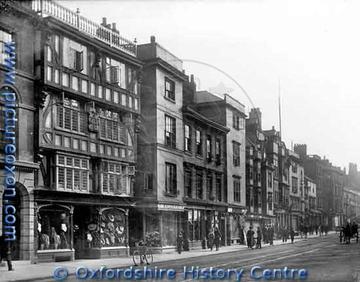

This is because the controversial statue of Rhodes was not added to an existing building. Far from it - the Rhodes

statue crowned a whole new Oriel extension, the Rhodes building, that was built between 1909 and 1911. This new Oriel extension was not built on undeveloped empty land. The Rhodes building was built on Oxford’s High Street, which was made up of rows of bustling shops and living spaces. More specifically, prior to 1909, the land on which the Rhodes Building now sits was occupied by the homes and shops of 95 to 101 High Street.

At number 95 High Street was the milliner, Miss A.K Baughan; at number 96 was the cutler, Frank Thomas Long; at number 100 was the optician Edwin Saunders; numbers 97, 89, 99, and 101 were also occupied by tenants or shopkeepers.[3] In turn, in 1909 – in order for the construction of the Rhodes building to go ahead – all of these tenants were forced out, and all the shops and homes of 95-101 High Street were razed to the ground.

Following the demolition of these buildings, the construction of Oriel’s extension was rapid; just over two years after construction began, on 28 September 1911, Oriel held an unveiling for their new building, the ‘Rhodes building’. Looking at the photos of the events the atmosphere appears celebratory. Oriel had gained a huge new extension that stood – in the words of Basil Champneys, the building’s architect – "in the most conspicuous position in Oxford"[4]. Moreover, Oriel lost little if anything in the process; Rhodes, in his will, gave Oriel £40,000 to build their extension – £17,500 more than the estimated cost of the extension – in order to compensate Oriel for any “loss to College revenue caused by pulling down of houses to make room for the said new college buildings.”[5]

Opening of the Rhodes Building

Oxford Journal Illustrated, 4 October 1911, Oxfordshire History Centre

The people of the city of Oxford had far less reason to celebrate. Rhodes left the city no compensation in his will. Likely for this reason, the jovial atmosphere at Oriel on 28 September owed much to who was invited and who was not. Journalists from the Oxford Times were certainly not invited – and were furious about being shut out. Two days after the unveiling of the Rhodes building, the Oxford Times, under the headline ‘PRESS BOYCOTTED’, lambasted Oriel for holding the event behind closed doors: “the reason why so much modesty and reticence [from Oriel College] as almost as to amount to secrecy was incomprehensible”[6] The anger of the Oxford Times stemmed from their belief that:

"Most people would have thought the opening ceremony in connection with a building in High-street, for which a whole row of shops and their tenants had to be removed, of such imposing dimensions as the Oriel extension, erected with money provided by the late Cecil Rhodes, would have been an occasion which demanded as much publicity as could be given it".[7]

The reason for Oriel's secrecy might have been ambiguous, but journalists at the Oxford Times were clear why they felt they should have been present at the unveiling: “It surely could not be that the authorities were so susceptible that they feared the critical observations that the new building might suggest, because their permission will not be necessary for what is so public and so obvious.”[8] The strength of this feeling echoed beyond the pages of the Oxford Times. Twenty-six years later, the Oxford resident W.E Sherwood wrote in his memoirs, that Oriel had “broken out into the High, … destroying a most picturesque group of old houses in so doing, and, to put it gently, hardly compensating us for their removal”.[9]

For W.E Sherwood the critique of the Oriel extension was aesthetic; for the Oxford Times, the reason for outrage was deeper. The Oriel extension represented Oxford colleges taking more public space from the city. The shops of 95-101 High Street had been part of the fabric of the city of Oxford’s community. In contrast, the Rhodes building - like the vast majority of buildings owned by Oxford colleges - became a private building whose high walls and locked door shut most ordinary residents of the city out. For this reason, on 7 October 1911, the Oxford Times – maintaining its polemic against Oriel – fumed: “It seems to be time that it should be challenged when the City is made to lose heavily by College improvements.”[10]

In this light, Rupert Fitzimmons's argument seems less convincing. It is hard to square the fact that erecting Rhodes’s statue was a controversial change to Oxford’s landscape, with the argument that we cannot take the statue down for risk of changing history. Yet Rhodes Must Fall would probably have replied very differently to Fitzimmons. RMF objected to Rhodes’s statue precisely because they believed Rhodes’s values and legacy – of white supremacy and imperialism - was not just part of the past, but rather, was part of the present.

Similarly, the conflict between the ‘town’ and ‘gown’ in Oxford is not confined to the past. As Danny Dorling, Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford points out, Oxford still struggles over land use, and between city and university demands.[11] Perhaps then, activists in the city – keen to challenge this – should not let criticism of Oriel be confined to the symbolism of Rhodes’s statue. Instead, activists might question the symbolism of the Rhodes building itself standing at all.

-- Blue Weiss

Blue Weiss read History at the University of Oxford, and completed his undergraduate degree in 2019. While at Oxford he was active in the Rhodes Must Fall movement and was also a member of Common Ground.

[2] Rhodes Must Fall was a decolonisation campaign that called for Rhodes’ statue to fall – among other demands.

[4] Brian Escott Cox, ‘100 years of the Rhodes building: its creation and re-appraisal’, The Oriel Record, (Oxford 2011)

[6] The Oxford Times, 30 September 1911, Oxfordshire History Centre

[7] The Oxford Times, 30 September 1911, Oxfordshire History Centre

[8] The Oxford Times, 30 September 1911, Oxfordshire History Centre

[9] W.E Sherwood, Oxford Yesterday. Memoirs of Seventy Years Ago, (Oxford: 1927)

[10] Oxford Times, 7 October 1911, Oxfordshire History Centre