This is a repost from Archaeology Archives Oxford to read the original post click here.

Posted on August 3, 2011 by Renasha Khan

In October of last year, an opportunity arose to examine the archive of Stuart Piggott. Having had long-standing interests in archaeology and history (especially in those relating to India and South Asia), I eagerly took the chance to explore documents and observations made by this influential archaeologist. My research paper ventures to assess the impact scholars, like Stuart Piggott, had on the changing intellectual history of archaeology. What is important to remember is that these letters were written in times of change and historical paradigm shifts, during World War II and the decline of the British Empire.

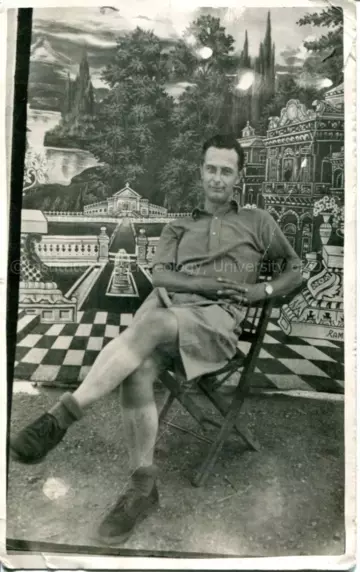

'Midnight on the palace terraces', Piggott in India, early 1940s. Archaeology Archives Oxford

A reluctant conscript, Stuart Piggott was assigned to the Military Air Photographic Intelligence corps in the RAF in 1942 and was posted to India. In November of that year and in September 1943, Piggott took leave for two visits to Sikkim, Tibet, and later Himachal Pradesh, Northern India. His ‘journal-letters’, written to his wife Peggy (Margaret Guido), elaborate on the changing geography and botany of his environment as well as giving insights into cultural and ritual traditions. We are given descriptions of local clothing, food, drink, and industry; these descriptions are interspersed with brief histories of the people they meet and the institutions they come into contact with, which preserve their place in British India. All seen through the eyes of an archaeologist. Whimsical prose and delightful ‘spit and scribble’ pictures of the landscape make these journal letters incredibly special, and I can honestly say that I’ve grown quite attached as I’ve studied them. What makes them extraordinary is the great shift in thinking they represent in the intellectual history of archaeology. Piggott was among many archaeologists and scholars who went to India and other colonial outposts for the war effort and who, despite their official duties, found the time to explore their academic interests. With this brought resurgence in the study of the prehistory of the subcontinent and on a broader view towards world prehistory. Piggott’s peers, including Glyn Daniel, Grahame Clark, Jaquetta Hawkes, O.G.S Crawford, and even his mentor, Vere Gordon Childe, ventured towards a new archaeology, looking outside the traditional scope of European prehistory.

The early 1940s was an interesting period in Indian and British colonial history as Indian Nationalism found its voice in widespread civil unrest under Gandhi and Nehru. The ‘Quit India’ movement was in full swing when Piggott leftNew Delhiin November 1942, so I was all too aware of the distinct omission of anything alluding to these political and social upheavals. Suspicious as this is, one has to remember that wartime correspondence would have been monitored heavily so Piggott would want ensure his letters got home, though conjecture on the links between archaeological pursuit and espionage during World War II is always entertaining! But mere speculation it is, so we must satisfy ourselves with what we have in front of us, and frankly we’re very lucky.

The Piggott archive, and in particular the journal-letters from India and Tibet, provides an insightful look into the talent, humour, and enterprise of one of the ‘wise men’ of archaeology. Writing my paper has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life, and as it draws to its inevitable end, I can truly say how honoured I feel to have had access to all these valuable historical sources. However, the mission continues as we endeavour to show people the wonders of our collection and the impact these people and their work had on the development of the intellectual history of archaeology with the upcoming exhibition, articles and events. Stay tuned in for more!