Veins of Influence through Views of Ceylon – Narratives of A Collection

An inter-disciplinary investigation of colonial images from Ceylon

Shalini Amerasinghe Ganendra is an Associate Academic of the History of Art Department and Visiting Scholar, St. Catherine’s College, University of Oxford. She was a Visiting Fellow at the Pitt Rivers Museum and Visiting Scholar, Wolfson College, during which time she researched the collection to be discussed. She is developing study on colonial images from Ceylon and the veins of influences, a term coined by her, of image on narratives of identity. The short analysis that follows is a precursor to a detailed article and presentation on this collection, in the Pitt Rivers Museum, and related findings.

The use of photography as a scientific and commercial tool was well established in Ceylon by the end of the 19th Century. The camera was used in archaeology, astronomy, anthropology, agriculture, engineering and industry between 1860 and 1880, [1] as well as in commercial studio practise. However, photographs of colonial Ceylon were and remain much fewer than those documenting its favoured colonial neighbour, the Jewel in the Crown, India. In India, photography had been officially and extensively employed, supported with funding, since the early 1860s. In contrast, there is little evidence that this more scientific application of the medium was widely employed in Ceylon.[2] The colonial images of Ceylon, located by the writer to date, are few and far between. Most show landscapes and locations, and those images of locals are done in the anthropological oeuvre of the times, with archival classification of ‘Natives’ or ‘Ethnography’, showing clear sensibilities of scientific study and ‘other’. The marked exception to such personal images would be the images of Julia Margaret Cameron, who lived the last years of her life in Ceylon, photographing mostly plantation workers, in her signature compositional style.

Key photographers operating during this time and covering Ceylon, either traveling or having a studio presence there, included: Bourne & Shepherd, Henry Cave, Colombo Apothecaries, Frederick Fiebig, Joseph Lawton, Lawton & Co. (Svaminathan Kanakaretnam), Plate & Co, Scowen & Co. and Skeen & Co. Plate & Co. continues as a studio and archival presence in Colombo. Notably, most surviving collections and images are located outside Ceylon (eg, UK, Europe and USA) and assuredly exist today as a result of being thus protected from the devastating effects of tropical weather on this medium.

Scholarship and recent exhibitions of colonial photographs from Ceylon, to date, (of which there is a dearth), however, have focussed on image classification, the relevant photographers and their individual practises. Departing from that didacticism, I outline here the dynamics in collection and collecting, with a broader consideration of how the collection might have interacted with ‘oscillating potentialities’ [3] beyond the collection materials themselves, to create and reflect what I term ‘veins of influence’ Veins of influence signify any material influence which intersects with the idea or object under review to add new life, perspective and dimension to the consideration, whether through networks of people, objects, practises, ideas and so forth.

This essay covers the finding of an unstudied collection of colonial-era photographs and related materials on Ceylon, in an album titled Views of Ceylon, (the ‘Collection’), held by the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University. This collection, largely unstudied, serendipitously provides a case study for tracing narratives of influence that operate from image to person and person to image. Here, I recreate networks of individuals and their relationship to the various images, providing an example of the ways in which imperial networks can be traced through university collections and the veins of influence that are revealed through these collections. Various revelations have unfolded through a review of these materials, their purported collectors, owners and creators, to reveal surprising significance with promise for further inter-disciplinary engagement, including for curatorial development and discovery of more veins.

THE COLLECTION:

Image 1. Album Cover

Provenance, Owners and Collectors

The initial anonymity of this collection necessitated a tabula rasa approach to the analysis, with no knowledge of provenance chain, content creators or collection relevance. The Collection’s route to the Pitt Rivers Museum (or PRM) (in 2010) remains unconfirmed. The Collection materials refer to five names L.A.S. Jermyn, ‘C.F.G.C.’ (shown to be Constance Francis Gordon Cumming), C. Symons, and in unclear script what may read as: Revd Cliff Godwin and J Lawton. The starting point is L.A.S. Jermyn.

L.A.S. Jermyn ( 1880 - 1962), Donor

Lancelot Ambrose Scudamore Jermyn (‘L.A.S.’), was born in Lucknow, India where his father served as a priest. After study at Keble College, Oxford University, he became a teacher, spending time in Malaya in the late 1930’s through to the 1940’s, the relevance of which we will see later. There is, however, no record of any visit by him to Ceylon.

Despite the notation ‘Presented by L.A.S. Jermyn’, we still do not know who the immediate recipient of that presentation was. The PRM accession note states that the Album came from the School of Geography but there is no record of when that School received the Album. [4] It is more probable that L.A.S., with no immediate male heir (as his son died young and childless as a soldier in war), gifted the Collection to Keble, his Oxford College, before his death in 1962. Keble College, with strong ties to the School of Geography, could have passed the materials on for greater access and appreciation.

Rt. Rev. Hugh Jermyn (1820 - 1903), Collector & Owner

The intersection between L.A.S. Jermyn, the Collection and Ceylon is certainly legacy: his paternal grandfather, Bishop Hugh Willoughby Jermyn, was the Bishop of Colombo from 1871 -1875.

Based on his dates of residence in Ceylon and proposed dates for most of these collection materials, it is likely that Bishop Jermyn was the primary collector and original owner of the Views of Ceylon Album (though likely not of all materials in the Collection).

Collecting and Creation

The Collection consists of :

- 1 vignette print of vine/flower fixed on inside first page, signed C Symons 1873;

- 44 albumen prints (each approx. 28cm x 21.5cm). 37 fixed on consecutive individual pages, followed by 7 fixed in different arrangement (front and back of each page). These 7 are roughly the same size as the previous 37;

- 2 photographs, cleared coffee plantations, fixed on one face page;

- 4 photographs of illustrations, , affixed on one face page.

- Loose, handwritten ‘Liste of Photographs’ – one page with notations on both sides

in two different scripts (‘Liste’);

- Loose, 1 studio photograph of turbaned man (‘Portrait’);

- Loose, sepia toned original painting, handwritten title and notation ‘C.F.G.C.’ (‘Drawing’)

- Leather bound album with gold embossed title Views of Ceylon, photographs pasted on pages, with numerous unused pages,

(collectively referred to as the ‘ Collection’ or ‘Jermyn Folio’. Materials pasted in the Views of Ceylon album are referred to as the “Album’. All materials are unsigned except where otherwise indicated.)

i) The Albumen Prints

The majority of the albumen prints in this Album capture the picturesque, showing rolling hills, exotic rock formations and tall waterfalls. We also see botanical focus with lush greens, ferns and palms – landscapes of a tropical paradise.

These first 44 albumen prints can confidently be credited to Joseph Lawton, a renowned British studio photographer active in Ceylon in the late 1860’s and early 1870’s. The dates of his commercial studio activity and stay in Ceylon overlap with Bishop Jermyn’s four years there.

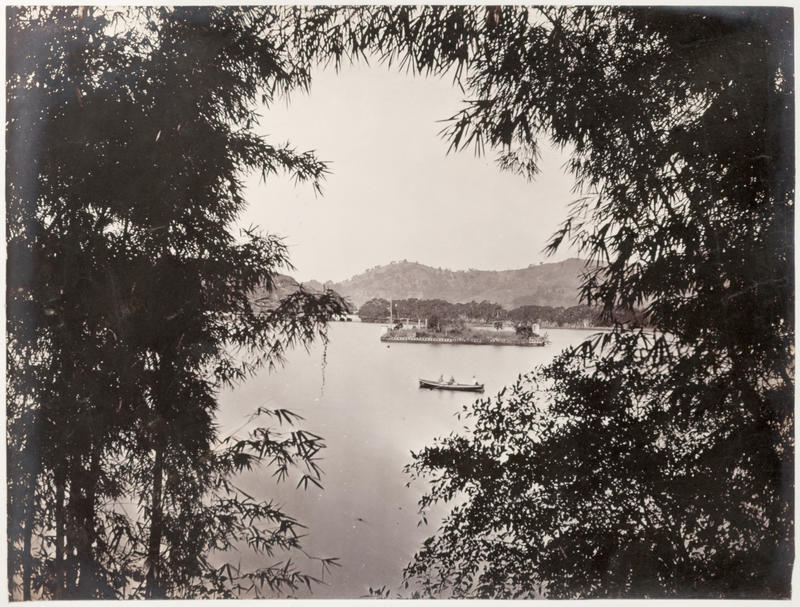

The views (the ‘Lawton photographs’) bear a striking, and in some cases exact, resemblance to photographs in The Princeton Art Museum Collection specifically titled Lawton, Views of Ceylon (1872-73), containing 25 albumen prints (the ‘Princeton Album’).[5] The photographs from both collections show similar perspectives with centralised focus, balance of dense and open spaces, and an eerie distancing of man from his environment. Both collections share six identical images including that of the Kandy Lake (shown below). [6]

Image: Kandy Lake, 2010.75.43.4 (page)-R (#4) Courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum

Notwithstanding Lawton’s importance as a colonial photographer, there is surprisingly little biographical information on him, including no confirmed portraits, birth year, or death dates. His legacy has been memorialised through his imaging of Ceylon.

The Jermyn Folio has no visible markings of or signings by Lawton, unlike the prints in the Princeton Album [7] and Victoria & Albert Museum Collections, which materials specifically refer to Lawton. It could be said that for this collector, the photographer’s identity was not material. His focus was on the images themselves.

Nawalapitiya Rd, Adams Peak. 2010.75.43.9 (page)-R (#9)

Ranboda Falls, 2010.75.43.30 (page)-R ( #30)

If this Collection started with the first 26 photographs as the Liste titling suggests, then it is arguable that additions were made in groupings by Bishop Jermyn during his four-year sojourn in Ceylon (during which time Lawton’s studio would have operated). As the photographs are not unique, they are likely from the studio’s commercial inventory rather than by special commission.

ii) The Drawing and Photographs of Illustrations:

Departing from photographic focus, the Collection features one painting signed ‘C.F.G.C.’, (Constance Frederica Gordon Cumming), which has been confirmed to be the original for an illustration in her publication Two Happy Years in Ceylon (the ‘Book’). We can only speculate how this original came to be included, whether gifted by Gordon Cummings or appropriated by other means. The artwork is loosely placed without being fixed to any page, though its trace imprint is found on many empty pages. Also pasted on one Album page are four poor quality photographs of four illustrations from the same publication[8]

Gordon Cumming published Two Happy Years in Ceylon documenting her extensive travels with the Bishop and his daughter, around Ceylon. Gordon Cumming aimed to share remote parts of the world for the benefit of people who were never likely to see such places for themselves. ‘In this, she offered reassurance as well as instruction and diversion,’ using the picturesque as propaganda.[9]

Avenue of Indian Rubber Trees, Ficus Elastica at Peradeniya, Ceylon. C.F.G.C.

2010.75.43.53 (mounted)-O [loose painting][10]

With clear intentionality of purpose through her painter’s hand [11], she recreated this ‘large and careful study of the magnificent avenue of the old india-rubber trees just outside of Peradeniya Gardens’ which avenue offered such ‘stately and unique approach’ into the Gardens.[12] The image serves to show more than just ‘prized beauty’[13], capturing the reader’s attention to then inform of the commercial viability of its rubbery sap writing that the ‘ever-increasing demand… would certainly be satisfactory if their cultivation in a British colony can be made to pay.’ [14]

Given the placement of the original and illustrations in this Collection, it is natural to wonder what the points of intersection might have been between the Lawton photographs and Gordon Cumming’s eye. What veins of influence from his images might have touched her views? How might she have intersected with his photographs?

iii) Views of Ceylon –The Anomaly:

Reviewing these Album pages, a viewer would have been justified in thinking the colony of Ceylon was a beautiful, abandoned isle, devoid of human habitation, with religious sites left as trace evidence of civilization. Nowhere in the Album pages do we see a person.

Had the collector so wanted, he could have added local identities onto the Album’s many empty pages, selecting from commercial studio stocks of ‘Ethnographic Studies’ or ‘ Native Types’. [15] The absence of such image offers yet another perspective on the collecting exercise. Perhaps the selected images, freed of people, showed distance between man and environment to more convincingly speak of God’s land; or maybe the Bishop just wanted to maintain content that reflected the literal classification of views of Ceylon.

Portrait. Man wearing a turban, carte . Loose

Hence the exaggerated and initially misleading significance of the one image of this man, placed loosely between the Album pages – an anomaly. Who was he? This most ‘personal’ image is in fact an impersonal commercial carte, printed in multiple, to be also found in the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands described there as ‘studio portrait of a man wearing a turban, carte’ from Singapore, circa late 19th/early 20th century). [16] The man was not even from Ceylon.

Through this carte, however, we find a possible trace of L.A.S. Jermyn’s contribution to the Collection. We can only speculate as to why this loose addition was made, through whom we experience for the first and only time in this collection, someone looking back at us.

CONCLUSION:

This Collection reveals numerous, magically interwoven human stories, manifesting various veins of influence. Nearly 150 years have passed since Bishop Hugh Jermyn’s stay in Sri Lanka. The Lawton photographs would be at least that old and remain well preserved away from the harsh, tropical environments that their origins would have offered. With important collection attributions including: key church figure, Bishop Hugh Jermyn; seminal photographer, Joseph Lawton; renowned Victorian-era artist and writer, Constance Frederica Gordon Cumming; and noted educator, L.A.S. Jermyn, the materials are a rich resource for continuing inter-disciplinary research and study of colonial Ceylon.

The selection of these particular images not only reflect a personal journey to and memory of the sites, but also a larger commitment to the Empire’s power over land and religion.[17] Further still, the idealised images of lush landscapes with their edenesque sensibility[18] belie the challenges of climate and illness that many a colonial succumbed to, including, ironically, both collector Bishop Jermyn and creator Joseph Lawton. [19] [20] We also do not see in this collection Lawton’s iconic archaeological images, perhaps an indication of this collector’s preference for natural landscapes and living institutions rather than impressions of ‘perpetual antiquity’ often associated with the imaging of Victorian-era Ceylon. [21]

Fortuitously and finally in the public domain, the Jermyn Folio materials can offer and realise their own deserved and unfolding narrative, to further extend the veins of influences revealed in the collection through, inter alia, the people, ideas and objects that have already been discovered and still await discovery.

REFERENCES:

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. BBC & Penguin, 2009.

Chua, Bok Chye. Our Story: Malacca High School, 1826-2006, 2006.

———. Two Happy Years in Ceylon. Vol. 2. 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892.

———. Two Happy Years in Ceylon. London: Chatto & Windus, 1901.

Gower, H.D. The Camera as Historian (1916). FA Stokes & Co., 1916.

Jermyn, L.A.S. The Singing Farmer. A Translation of Vergil’s ‘Georgics.’ Oxford: Blackwell, 1947.

Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1870-1874, Proceedings 1872.

Laracy, Hugh. Watriama and Co: Further Pacific Islands Portraits. ANU E Press, 2013.

Lawton, Joseph. Princeton University Art Museum Collection, Lawton/Views of Ceylon.

———. The Coming of Photography in India. The British Library, 2008.

IMAGES

All images courtesy Pitt Rivers Museum Collection (except where otherwise stated) and include catalogue reference in title. All rights reserved.

[1] Ismeth Raheem, Thoma Percy Colin, Images of British Ceylon: Nineteenth Century Photography of Sri Lanka (Times Editions, 2000).

[2] John Falconer, Regeneration, A Reappraisal of Photography in Ceylon 1850-1900 (British Council, 2000), 17.

[3] Christopher Pinney, ‘Foreword,’ in Visual Histories of South Asia, First Edition (Primus Books, 2018), xii.

[4] Discussion with Susan Squibb (a.k.a. Sue Bird),Retired Geography Subject Librarian,Bodleian Libraries, Oxford University, March 23, 2020.

[5] Joseph Lawton, Princeton University Art Museum Collection, Lawton/Views of Ceylon., n.d., n.d.

[6] Accession note states: Joseph Lawton, British, d. 1874. Views of Ceylon, 1872–73. Gift of Jerry N. Uelsmann.

[7] Princeton Album has embossed in gold lettering on the cover, Lawton, Views of Ceylon. Compare also V&A Lawton Collection, photographs from the special commission by the Ceylon Archeological Committee. Those photographs show LAWTON’ on right corner of each image.

[8] C. F Gordon Cumming, Two Happy Years in Ceylon, vol. 1, 2 vols. (Edinburgh and London,: W. Blackwood and sons, 1892).; C. F Gordon Cumming, Two Happy Years in Ceylon, vol. 2, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892). Gordon Cumming, Two Happy Years in Ceylon, 1901. London: Chatto & Windus, 1901.

[9] Laracy, 85.

[10] Gordon Cumming, 187.

[11] Pinney, The Coming of Photography in India, 2–3.

[12] Gordon Cumming, Two Happy Years in Ceylon, 1901, 187.

[13] Gordon Cumming, 187.

[14] Gordon Cumming, 188.

[15] Raheem, Thoma, Images of British Ceylon: Nineteenth Century Photography of Sri Lanka, 44.

[16] Unknown, Rijksmuseum. August Sachtler Collection. Studio Portrait of a Man Wearing a Turban, Singapore circa 1870-1900. Carte de Visite. Object No: RP-F-00-5225 LL/76427.

[17] Falconer, Regeneration, A Reappraisal of Photography in Ceylon 1850-1900, 11.

[18] Vindhiya Bhuthpitiya, ‘‘Paradise’ in Missing Pictures: A Brief and Incomplete History of Sri Lankan Photography,’ History Workshop, July 2019, 2.

[19] Lawton around 1872, and Jermyn in 1875.

[20] Beven and Martensz, A History of the Diocese of Colombo, 42.

[21] AnnaMaria Motrescu-Mayes, ‘Perpetual Antiquity in Early Photographs of Ceylon,’ in Visual Histories of South, First (Primus Books, 2018), 93–123.