‘Only a thickness of wall’: Empire and Oxford in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure (1895)

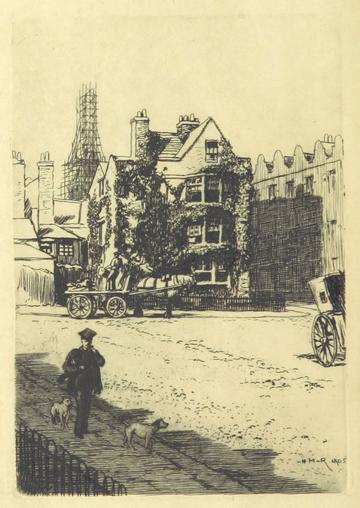

H. Macbeth-Raeburn - ‘The “Christminster” of the Story’. Illustration on the title page of Jude the Obscure ([London:] Osgood, McIlvaine and Co., 1896). British Library online collection, ref: Digital Store 012624.h.25/8

Empire is everywhere in Jude the Obscure, but it is the Roman and not the British one. Ancient Rome pervades the novel, from its lived traces in the landscape to its cultural legacies,1 while by contrast the British Empire is acknowledged only in passing. This is notable in that the book was written during what has been called the height of Empire, when imperial expansion was driving drastic shifts in British society, among them large-scale emigration.

Indeed, the Empire’s main intrusion into the plot is the sub-narrative of Arabella’s emigration to Australia. Jane Mattison has compared this episode to the earlier emigrations of characters in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield (1849-50) and Great Expectations (1860-61), highlighting how taken together they illustrate a shift in British perceptions of Australia, as well as in migration patterns.2 However, the colony itself is sketched only minimally, and it would seem that its primary function – besides getting Arabella out of the way for a while – is to establish an axis stretching from the metropole to its remotest colony.

It is in terms of this axis that Hardy frames Jude’s feeling of exclusion once he moves to Christminster/Oxford3 for the first time. Having come as close as spatially possible to the object of his life’s mission, Jude perceives he is still irrevocably excluded from it: ‘Only a wall divided him from those happy young contemporaries of his with whom he shared a common mental life… Only a wall – but what a wall!’4 Notwithstanding this claim to intellectual kinship, ‘he was as far from them as if he had been at the antipodes.’5 The storied walls of Christminster are as imposing a barrier as thousands of miles of ocean. Perhaps more imposing: after their separation, Arabella travels from Marygreen to Australia and back again, but Jude fails to gain access to the University.

By positing an equivalence between Jude’s status and that of someone living at the furthest extremity of the British Empire, Hardy outlines a vision of empire premised on inclusion and exclusion more than geographical location. He employs this forceful metaphor once again at the end of the novel, when Jude and Sue return to Christminster. They find themselves in a narrow lane behind a college; the narrator comments that, within it, ‘life was so far removed from that of the people in the lane as if it had been on opposite sides of the globe; yet only a thickness of wall divided them.’6

This effect was deliberately cultivated, of course. As Jane L. Bownas observes in her groundbreaking Hardy and Empire (2012), many Oxford students would go on ‘to serve the Empire on the “opposite side of the globe”, and remain as separated and removed from the inhabitants of the countries which they occupied as they had been from the inhabitants of the lane in Christminster.’7 Jude’s exclusion from Christminster could thus be taken as an effect of what Bownas calls the ‘domestic replication of the relationship existing between the metropole and its far-flung colonies’.8 This established a certain conceptual equivalence between domestic and foreign proletariats, as Hardy suggests, although Daniel Bivona may be somewhat reductive when he argues that Hardy depicts ‘a society committed to colonizing its rural lower classes as it is colonizing the dark races of the world’.9

Jude himself is oddly oblivious to this geopolitical dimension of the University, as is made clear during his heady first night in Christminster. His vision of spectral ‘sons of the place’ dwells on poets, philosophers and historians, but passes quickly over ‘official characters – such men as Governor-Generals and Lord-Lieutenants, in

whom he took little interest’.10 On the face of it, the novel takes as little interest as Jude does in the imperial role of Christminster/Oxford. But by positing an equivalence between the socially displaced Jude and the spatially displaced colonial subject, Hardy makes an oblique comment on how colonial authority is reproduced and maintained both at ‘the antipodes’ and in ‘the heart of the heart of the Victorian empire’.11

This text was inspired by conversations with my colleagues on the MSt in Literature and Arts – we have been exploring the cultural legacy of the University through different interdisciplinary approaches.

1 See Jane L. Bownas, Thomas Hardy and Empire: The Representation of Imperial Themes in the Work of Thomas Hardy (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), chapter 2, ‘Roman Invaders: the Rise and Fall of Imperial Powers’.

2 Jane Mattisson, ‘To Australia and Back. The Metaphor of Return in Dickens’ David Copperfield and Great Expectations and Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure’, Nordic Journal of English Studies, 2(1) (2003), 129–143. I am grateful to my colleague Amy Norton for this reference.

3 Christminster is Oxford seen as if in a dream, as Sue Brideshead remarks of the Apocrypha, ‘when things are the same, yet not the same’. Jude the Obscure, IV.i, 242 (this and following references are to the 1994 Penguin Books edition).

4 Jude the Obscure, II.ii, 102.

5 Jude the Obscure, II.ii, 102.

6 Jude the Obscure, VI.i, 393.

7 Bownas (2012:22). Rena Jackson’s work has since expanded the field; see for example her recent ‘African adventure and metropolitan dissent in Thomas Hardy’s Two on a Tower (1882)’, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 56:1 (2020), 126-139.

8 Bownas (2012:19).

9 In Bownas (2012:21). As Rena Jackson observes regarding Hardy and Empire, the ‘propensity to analogize rural plights to colonial oppression… at times flattens different realities of imperial deracination and leaves the persistence of social inequalities within colonial space unaccounted for’. Rena Jackson, ‘[Review] Thomas Hardy and Empire: The Representation of Imperial Themes in the Work of Thomas Hardy’, Thomas Hardy Journal 29 (Autumn 2013), 176-181, p.180.

10 Jude the Obscure, II.i, p.95.

11 Antoinette Burton, At the Heart of the Empire: Indians and the Colonial Encounter in Late-Victorian Britain (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p.114.

John Gray is a writer and curator based in Berlin. Recent projects include the book Cassette Cultures (Benteli, 2019), a study of the cassette tape as a media format, and the exhibition 'Druck Druck Druck' (Galerie im Körnerpark, Berlin, April-August 2019), showcasing independent print communities from Berlin and beyond. This text was inspired by conversations with his colleagues on the MSt in Literature and Arts.