The Bodleian Shuinjō: Early English Trade with Japan, 1613-1623

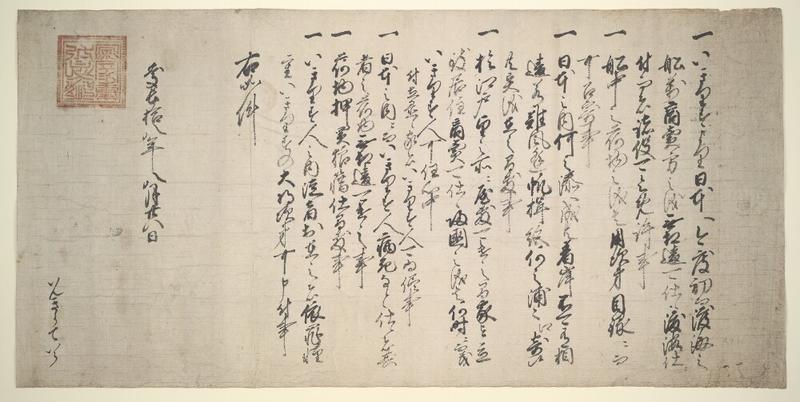

This document from the Special collections of the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford is a shuinjō or ‘vermilion seal trading pass’, granted by Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu of Japan to merchants from the English East India Company (EIC) in 1613. Its brief contents bestow upon the English the right to conduct trade with the Tokugawa state and to establish a trading post, known as a factory, on Japanese soil. The English would engage in trade with Japan between 1613 and 1623, until poor returns and pessimistic prospects caused the EIC to close the factory for good.

Shuinjo, Tokugawa Ieyasu, 1613, Bodleian Library MS. Jap. b.2, Photo: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, 2020

The Company’s Origins

Although perhaps best known for its colonial activities in India and Southeast Asia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the origins of the East India Company (EIC) lie in the European expansion into the Asian spice trade in the seventeenth century. Initially dominated by Spanish and Portuguese merchants, the trade in spices such as pepper, cloves, and nutmeg proved a tempting prize for English merchants, who in 1600 received a royal charter for a ‘Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies’. Amongst the founding members of the fledgling East India Company was Richard Hakluyt, author of the Principal Navigations of the English Nation and graduate of Christ Church College, Oxford.

The Company’s role in this early period of overseas enterprise was not yet one of colonial domination; its charter asserted that its purpose was ‘the Increase of… Navigation, and Advancement of Trade of Merchandize’. The merchandise of most interest to the Company and its stockholders were the spices available in South-East Asia, a market dominated in this period by the Spanish and Portuguese maritime empires. Access to the spices of the Moluccas and Coromandel Coast required involvement in the intra-Asian trade, where spices could be bought for gold from Sumatra, Indian textiles, Chinese silks and Japanese silver. Japan, the second-largest producer of silver after the Spanish American colonies, was a tantalising prospect for the early EIC.

William Adams: English Inroads

Not only was Japan a tantalising source of silver for the English, who lacked the direct access to American silver enjoyed by the Spanish, but they also had a convenient link to the country in the form of William Adams. Adams, a Kentish shipwright and pilot for one of the precursors (voorcompagnien) to the Dutch East India Company, had been stranded in Japan since 1600 when his ship, de Liefde, was wrecked on the coast of Bungo province. Unlike many of his shipmates, however, Adams had prospered, proving himself of interest to the newly acceded shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu. Until this period, Japan’s official interactions with Europe had been conducted through Iberian merchants and missionaries; Ieyasu saw in Adams a counter-narrative to the image of Catholic Europe they promoted. Rewarded for his service to the shōgun with a fief and the samurai title of hatamoto (bannerman), Adams was optimistic that the English would prosper in Japan. Upon discovering that his countrymen intended to trade with Japan, he reassured the EIC agents in Java that ‘There has not been, nor shall not be, a nation more welcome’ than the English.[1]

Opening Trade: The Bodleian Shuinjō

On 11 June 1613 the EIC vessel Clove arrived in the harbour of Hirado, a small port town on the northwest coast of Kyushu. The captain of the voyage, John Saris, and his chief merchant Richard Cocks were greeted heartily by the local feudal lord or daimyo, Matsūra Takanobu. After travelling to Tokugawa Ieyasu’s court, Saris and Adams presented the former shōgun – now the power behind his son’s throne – with a letter from King James VI and I, formally requesting trade with Japan. In return, on 8 October 1613, the English were granted two copies of the shuinjō trading pass, authorising them to establish a factory, bring goods to Japan, and conduct such discipline of English merchants as Cocks deemed appropriate.

Shuinjō were precious documents; without them, merchants were unable to engage in foreign trade. Ships which did not carry a shuinjō were considered smugglers and lawful prize for privateers. Amongst the English, they were taken as physical representations of their right to trade, and were frequently invoked when resolving disputes with Japanese individuals. When a group of Japanese kabukimono (rabble-rousers) boarded an English junk in 1617, William Adams produced his shuinjō, ‘kissing it and holding it up over his head’ in an attempt to invoke the Shōgun’s protection.[2]

English Policy in Japan

The reliance of the English upon the privileges granted to them by the Japanese government suggests that, unlike its eighteenth- and nineteenth-century counterpart, the EIC of the seventeenth century was reliant upon the favour of local rulers. It did not, in this early period, command a fleet or military capable of enforcing its will in the East Indies. While the unfulfilled promise of access to the Chinese silk market through the merchant-pirate Li Tan was a spectre which haunted the factors for the duration of their time in Hirado, the English lacked the trade goods that Japan desired most. Much of the trade with Japan was in Indian cloth – chintz and calicoes – as well as English broadcloth, tin and lead. None of these goods were particularly desirable to the Japanese market, and within only a few months the English were already aware of the challenges facing them. ‘Could we get any great quantity of broadcloth to vend,’ Richard Cocks wrote in November 1613, ‘it would prove a great matter… in the meantime we must seek out other matters beneficial.’[3]

While the search for profitable goods continued, the English factors made up for their poor returns by immersing themselves fully into the cultural world of Japan. All too aware of the weak position from which the English negotiated, Richard Cocks advised his merchants to ‘make much of friends when you have them, and use [the Japanese] kindly… for fair words will do much and as soon are spoken as foul, and always good will come thereof.’[4] In this, he led by example, hosting dinners for his Japanese neighbours and the local nobility, entertaining them with kabuki performers, and observing local festivals, including New Years’ celebrations and Obon, the feast of the dead. Although a devout Christian, he found much to admire in Shinto-Buddhism, writing that the Japanese were noteworthy in their ‘liberality and devotion’, and that the Hōkō-ji temple in Kyoto was ‘to be reckoned before any of the noted 7 wonders of the world.’[5] The good relations which the English held with their Japanese neighbours are reflected in letters sent to the merchants by their friends following their departure in 1623: ‘I cannot forget the friendship you showed me while you were here,’ one wrote, ‘and I constantly wish that you might come back to Japan once again.’[6]

In trade as in socialising, the English were compliant visitors to Japan, unable to protest when the shuinjō privileges were curtailed in 1616, restricting trade only to the port of Hirado. As elsewhere in Asia, the merchants were expected to present the shogunate with annual gifts in return for continued trade, a practice which Cocks resented, complaining that the Japanese ‘encroach, and ask but give nothing’, to the point where in 1622 he considered that ‘nothing of worth rests to give.’[7] Attempts to follow the Dutch example and use Hirado as a base for plundering Iberian shipping as a source of profit proved treacherous when the Nagasaki administrator Hasegawa Gonroku sought to use the practice to draw European profits away from Hirado and towards the Portuguese trade at Nagasaki. The English were entirely reliant on the daimyo of Hirado to support their case, noting that ‘if we get no redress for these matters, it is no abiding for us in Japon’.[8]

Ultimately, however, the inability of the English to abide in Japan came not from Edo but from London. In 1623, citing heavy debts and incomplete accounts from Hirado the EIC ordered the closure of the factory and the immediate withdrawal of its merchants. On 24 December 1623, the factory doors closed for the last time, and the EIC vessel Bull departed for Batavia.

Hirado to Oxford in the Seventeenth Century

Long before the English factors at Hirado were recalled, however, documents from the English factory had made their way back to England and into the collections of the University of Oxford. Following the sealing of the 1613 shuinjō, the two copies of the document were separated. One copy was to remain with Richard Cocks in Japan; the other would be returned to England by Saris in 1614, where it would disappear from the records. By 1680, the shuinjō had reappeared in the Bodleian Library, erroneously listed as a Chinese manuscript. In 1697, the document had been recategorized, again inaccurately, as a ‘Japanese edict forbidding the sale of goods before dues are paid.’ Although the reason for this change is unknown, Derek Massarella has suggested that it was due to the translation efforts of Shen Fuzong during his cataloguing of the library’s Chinese-language material.[9] In 1620, the Bodleian also received, through the donation of Sir Henry Savile, the manuscript to William Adams’ logbook, detailing the pilot’s travels to Siam and China in the service of the EIC between 1614 and 1619.

Prelude to Empire

Through the Bodleian shuinjō, we are given a glimpse into the early history of the East India Company, in a period before the development of military and economic strength enabled the Company to assert itself as an imperial and colonial power throughout Asia. The conditions of trade marked out by Tokugawa Ieyasu would form the basis of a ten-year relationship during which the English would rely heavily upon the advice, assistance and intervention of Japanese citizens of various social ranks in order to keep their factory afloat. Unable to use force to assert their position, English merchants adopted – at times unwillingly – a policy of assimilation and integration through which they hoped to negotiate better conditions whilst waiting, in vain, for more profitable goods to sell.

The Bodleian’s collections also offer insight into Oxford’s position as a repository of knowledge about early global encounters. Even as English sailors and merchants were beginning to strike out to foreign lands in search of profit, the Bodleian provided a centre for the collection and collation of materials concerning the places and peoples encountered by English agents overseas. The materials from Hirado formed but one part of a broader collection of documents and artefacts from sites of English enterprise abroad, from the Americas to the Levant to the Pacific, where glimpses of a widening world might be assembled and organised in microcosm.

[1] Anthony Farrington, The English Factory in Japan, 1613 – 1623, (2 vols. London, 1991), i, p. 76 (William Adams at Hirado to Augustine Spalding at Bantam, 12 January 1613).

[2] Richard Cocks, Diary Kept by the Head of the English Factory in Japan, 1615-1622 (3 vols. Tokyo, 1978), ii, p. 49 (22 March 1617).

[3] Farrington, English Factory in Japan, i, p. 99 (Richard Cocks at Hirado to the EIC in London, 30 November 1613).

[4] Ibid., p. 124 (Richard Cocks’ instructions to Richard Wickham, January 1614).

[5] Cocks, Diary, i, p. 337 (2 November 1616).

[6] Farrington, English Factory in Japan, ii, p. 957 (Mathias at Hirado to Edmund Sayers, 15 January 1624).

[7] Cocks, Diary, iii, pp. 230-1 (20 January 1622).

[8] Farrington, English Factory in Japan, ii, p. 850 (Richard Cocks at Hirado to the EIC in London, 30 September 1621).

[9] Derek Massarella and Izumi K. Tytler, ‘The Japonian Charters’, p. 196.

English translation of the Bodleian Shuinjō

Translated by Izumi Tytler, in Derek Massarella and Izumi K. Tytler, ‘The Japonian Charters: the English and Dutch Shuinjō’, Monumenta Nipponica 45:2 (1990), pp. 189-205.

Item The ships that have now come to Japan from England for the first time will be allowed to trade in all goods without hindrance; they will be exempted from customs and other duties.

Item As for the goods aboard, they should be listed separately according to their use and the list should be submitted.

Item Their ships shall be allowed to arrive in any port of Japan; if they lose their sails and helms owing to storms, there will be no objection to their coming into any inlet.

Item In due course a residence shall be granted to the Englishmen anywhere they like in Edo; meanwhile they may build a house and reside and trade there; as for their return to their own country, it is up to them. [At their departure] they should dispose of the house built by them.

Item If an Englishman dies of illness, or any other cause, in Japan, his possessions shall be sent forth [to England] without fail.

Item Forced sales by violent means shall not be allowed.

Item If any of the Englishmen commits an offence, he shall be sentenced according to the gravity of the offence; the sentences shall be at the discretion of the English commander.

Wherefore, as above.

Keichō 18, Eighth Month, 28th day.

Minamoto Ieyasu

Fidelity and forbearance.

Callum Kelly is a doctoral student in the History Faculty at the University of Oxford. His research examines the shape and nature of the encounter between English and Dutch merchants and citizens of Tokugawa Japan at the beginning of the seventeenth century. He draws upon a range of sources, including diaries and correspondence produced at Hirado as well as visual materials such as nanban folding screens, netsuke and lacquerware, synthesising the textual, visual and material to provide a detailed insight into the extended encounter between Europe and Japan. Callum is also a convener of the Transnational and Global History Seminar (TGHS) at Oxford, a graduate-led seminar focusing on a variety of themes in global history.